Coal Produced Before 1800

From Coal Commission Report 1871

The Scotch Coalfields. - There exist materials from which a good account of the collieries of Scotland might be written, especially as to the modes of working adopted, and the condition of the people employed. We are restricted, however, to a mere sketch, hoping that this work will be written by Mr. A. Giekie, director of the Geological Survey of Scotland, to whom we are indebted for some of the following notes.

Amongst the earliest reliable accounts of the Scotch coalfield we find that in the twelfth century William de Vetereponte granted to the monks of Holyrood "totam decimam de carbonario meo de Carriden." This is the name of a small brook flowing into the Firth of Forth, about three miles north of the ancient palace of Linlithgow. This was in the reign of William the Lion, during whose reign the monks of Newbattle worked coal on the margin of the Esk.

In the cartulary of the abbey of Newbattle there is a grant by Sayer de Quinci, Earl of Winchester, allowing the monks to work coal. In the year 1189 the father of this nobleman made over to the abbey the grange of Preston, with certain rights of pasture, peat, and fuel. Earl Seyer added to this gift a coal work. This was at the beginning of the thirteenth century, certainly before the year 1212.

We have numerous records of iron mining and smelting at an early date in many parts of Scotland. Probably the earliest record in any way connected with mining in relation to the province of Moray is contained in a charter, or, more properly, in the "Bulla Urbani IV. Monasterio vallis St. Andreas de Pluscardyn, concessa A.D. 1263." The cartulary of Holyrood records the tithe of iron and gold. And in 1124 and 1127 one seventh of the ore raised was brought to the king's works at Dunfermline; and before 1510 iron was paid as rent to the Earl of Sutherland and Monteith. But neither these particular charters, nor any of those which are to be found up to the beginning of the eighteenth century, bear on the production of coal, as wood-charcoal was probably the only fuel employed.

This is noted merely for the purpose of correcting an error sometimes committed. Coal is not unfrequently mentioned in connexion with those ironworks, and it has been assumed that "pit coal" was intended by the term, whereas a little care in examining the evidence would have proved that the coal was wood-coal or charcoal.

In 1291 William de Obervil grants to the abbot and convent of Dunfermline the right of opening the coal heugh on his land of Pittencrieft. From all the accounts preserved there were evidently small workings on the outcrop of the coal seams, - being, in fact, mere quarries.

In the year 1322 Bruce granted to Henry Cissor the lands of Kilbaberton "et illud carbonarium infra baroniam de Travernent, quod vocatur Gawaynes-pot." Chalmers states that from the age of Robert Bruce there is a series of charters granting collieries in East Lothian. David II granted a charter of the north part of the barony of Inverkeithing, "with the cold-heughe and milne of Graggeford." In this reign coal was used in the royal household. Eighty-four chalders of coal were purchased for the use of the Queen's retinue, costing twenty-six pounds. We find a charge at this time of twenty-six shillings and eightpence for twenty chalders of coal, with the carriage of them to Parliament.

The "coalieries of Tranent" were evidently well known in 1407, since we find several grants relating to them. The Fife miners were also successful in working coal. Henry de Sancto Claro, Earl of Orkney, granted to John Forstor of Corstorphine a wadset of twelve marks Scots out of the barony and collieries of Dysart in Fife; which grant was confirmed by Robert Duke of Albany, in 1406.

Chambers tells us the coal was exported from Scotland in the fifteenth century, but he gives no authority for the statement. Coal was, however, but little used, and only within a short distance of the collieries.

Hector Boece, writing in 1526, says-

"In Fiffe ar won black stanis, quilk has sa intollerable heit quhan thay are kendillit that they resolve and meltis irne, and ar thairfore richt proffitable for operation of smithis. This kind of blak stanis are won in na part of Albion bot Allanerlie, betwix Tay and Tyue."

Five years after the publication of Boece's history (1581) a formal agreement was made between the convents of Newbattle and Dunfermline, regarding the working of their coal in the neighbourhood of Pinkie. This document was printed by the Bannatyne Club.

In Sir David Lindsay's "Satyre upon the Three Estatis," written in 1535, there occur several references to the collieries of East Lothian as places which would be familiar by name to a large number of his readers.

The coal trade of Scotland had gradually risen to such importance that in 1563, the ninth Parliament of Mary, we find the following order that no coal are to be taken out of the country under pain of confiscation of ship and cargo :- " In consideration of the great multitude of coales continuallie caried forth of this realms, not only be strangers, bot alswa be the lieges and inhabitants of the samyn, quhilk is now becummin the common ballast of emptie shippes, and gives occasion of most exorbitant "dearth and scantness of fewall." This shows that coal must at this time have been raised in considerable quantities.

In the year 1579 the Scottish Parliament found it necessary to ratify and approve the previous prohibition, and offer a reward to the "reveiler and apprehender of the contravenors of the Acte."

Thirteen years afterwards the Parliament were still anxious to guard the interest of the collieries, and we find them passing an Act "for the better punishment of the wicked crime of setting fire in coal benches, be sum ungodly persones, upon privat revenge and despite."

The export of coal continued in spite of legislation, and evidently increased, the Acts of Parliament notwithstanding. In the year 1597 the King and his estate were given to understand "that the great burne coals are commonly transported forth of this realm be divers and sindry persons, &c." It was therefore enacted that "no grite burne coile (great burn coal, that is, coal in large pieces) should be "exported on any pretext," &c.; and the ships were to be confiscated, and the shippers kept in arrest, during His Majesty's pleasure. In 1598 we find the coal of the Brora seam worked for the purpose of supplying fuel for the salt-pans erected on the eastern coast of Sutherland by Lady Jean Gordon.

Coal mining progressed. The workings, however, were carried on without much method, with very imperfect machinery, and altogether under difficulties; many of them arising from a want of thought, many from a desire to adhere to the traditional methods of mining, and more really from the very imperfect machinery known in those days.

In the spring of 1621 we find the Privy Council settling the price of each horse-load of coal, and determining that it should not exceed seven shillings Scots, or seven-pence sterling.

We find the coal proprietors continue troubling the Privy Council in such a way as would lead to the conclusion that the collieries were not very profitable concerns, or that the proprietors were very grasping individuals. We have the Privy Council, upon the petition of the landowner, granting licences to export coal, and other advantages; which appear to have given them a close monopoly, and to have made the fortunes of many of them; but we cannot discover any records of the quantities of coal raised or exported in the 17th century.

The privilege of exporting coal without any excise duty was long enjoyed by the family of Halkit of Pitferrane, near Dunfermline. It was renewed by Queen Anne, and ratified by her Parliament in 1707. This family continued to possess it until 1788, when it was purchased from them by the Government for the sum of £40,000. Machinery had by this time been introduced into the Scotch mines; but gunpowder had not even yet been employed in working the coal.

For more than 300 years coal appears to have been worked around the town and neighbourhood of Culross. In the year 1510 we learn from the cartulary of Cambuskenneth that those collieries were subject to a tithe rent. In the 17th century the mining operations here were so extensive, and the fact of their being worked under the sea was esteemed so wonderful, that they became famous all the country over. James VI in 1617 visited this district, and descended the Culross Colliery, and as the story goes, was greatly terrified, fearing, as usual, treachery and assassination. This mine was sufficiently notorious to induce John Taylor, the water poet, to describe it particularly in one of his poems. In this he says, "They did dig forty feet down, right into and through a roche. At last they found that which they expected, which was sea-cole. They, following the veine of the mine, did dig forward still; so that in the space of eight and twenty or nine and twenty years they have digged more than an English mile under the sea; that when men are at worke belowe, an hundred of the greatest shippes in Britaine may saile over their heads."

According to Taylor's account 90 tons of salt were then made weekly at Culross, equal annually, at 40 bushels to the ton, to 180,000 bushels; a quantity, at one work only, equal to about three fourths of the whole quantity of salt now manufactured at the different salt-works on the Firth of Forth. Ninety tons of coal are stated in Lord Dundonald's letter to be required for making 360 bushels of salt, or 500 tons for the annual make. Large quantities of coal were said to have been sent to London from Culross in the years 21 and 22, while the Scots' army lay at Newcastle, and interrupted the trade of the river.

In 1678 Sir Robert Cunningham displayed much enlightened enterprise on the coast of Ayrshire, by introducing a series of extensive improvements upon his colliery of Saltcoates. Notwithstanding a grant from the Crown, the enterprise of Sir Robert was not rewarded as it should have been, as we find him in 1700 selling a large portion of his estate.

In 1690, in the Parliament of William and Mary, it was declared that the right of importing foreign commodities should belong only to the royal burghs, and that the corporations should enjoy the exporting of all commodities, except "corns, cattle, horses, sheep, metals, mineral coals, salt, lime, and stone."

About this time Newcomen's steam engine was introduced in Scotland for pumping water from the mines. Much additional information will be found in Bald's View of the Coal Trade, and in the New Statistical Account of Scotland.

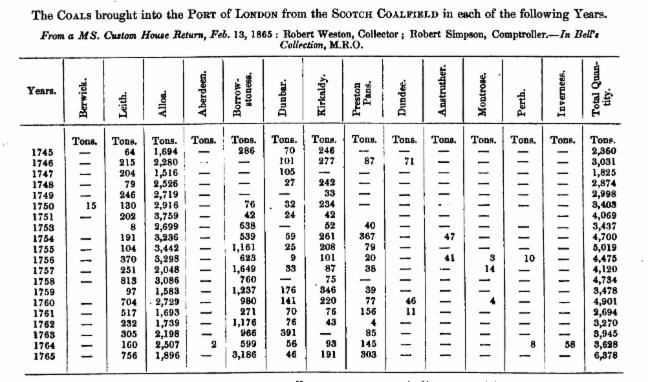

From 1745 we obtain a more exact return of the quantities of coal sent to London from all the several districts producing coal in Scotland until 1765. This will be seen in the following table:

The coal tax in 1793 pressed most unequally, and a strong feeling was rising against it. From letters addressed to Pitt we quote the following:-

"It appears from the Custom House books that the amount of the duty received in Scotland for coals brought coastways from January 5, 1790, to January 5, 1791, amounted to £10,237 2s. 7 ½d.; the quantity of coals so carried 55,838 tons 18 cwt. Duty from January 5, 1791, to January 5, 1792, £10,371 8s. 10 1/2d.; quantity of coals so carried, 56,571 tons 10 cwt.

| £ s d | |

| The duty on coals brought coastways from port to port in Great Britain is per chalder, Winchester measure 36 bushels | 0 5 6 |

| Ditto into port of London | 0 8 10 |

| Coals exported to Ireland, per chalder | 0 1 2 |

| To British plantations | 0 2 3 |

It will be seen by a Table given in Appendix that the best Newcastle coal was sold in the Firth of Forth at 35s. 6d. per chaldron of 54 cwt, and the best Forth coals at 24s. 3d.; and that at Aberdeen the best Newcastle was 35s. 6d., while the Forth coal was only 31s. the chaldron.

Some idea of the state of the coal trade at this time may be formed from the following statement relative to the estate of Lord Dundonald at Culross:-

"Four distinct and separate winnings may be made on different seams of coal, and the colliery at each wining may be carried to as great extent as any one colliery on the Forth. There is one colliery working only to the extent of 12,000 Newcastle chaldrons annually, which from Christmas 1790 to Christmas 1791 cleared of nett profit £3,385 at the then inferior price of coal."

It is not a little curious to find it asserted that the extension of ironworks will ruin the coal mines.

"The following statement is necesary to enable the public to judge of the injury, in one point of light, done to the coal owners by the erection of ironworks. There are two blastfurnaces at Muirkirk, two at Cleland, three at Carmile or Clyde ironworks, in all seven; of which there are five at present in blast. Each blast furnace, blown by a steam engine, consumes, including engine coals, workmen's coals, and coals for calcining the mine or ironstone, at least 9,000 tons of coal annually: inde, five blast furnaces will consume 45,000 tons. And as on an average each collier in Scotland does not turn out above eight tons of coal weekly, it will require 112 colliers to work the above quantity of coal, exclusive of other colliers and miners employed to sink pits, drive mines, and work the ironstone and limestone for the furnace. For these purposes it cannot take less than 150 additional hands; so that five blast furnaces will require 262 colliers and miners, formerly employed in preparing collieries for work, or in working coals for the domestic consumption of the inhabitants of Scotland. This evil is only beginning to be felt; it being certain, from the present high price and great demand for cast-iron, as well as from the peculiar advantages attending many situations in Scotland, that twenty additional blast furnaces will be erected in Scotland within the space of ten years from present date, requiring a supply of 2,048 colliers and miners.

Or, erectors of ironworks must be compelled to breed hands for their works, by being prohibited by Act of Parliament, by a bill to be brought in for the special purpose, from employing any colliers now employed at the collieries. [REPORT OF THE COMMISSION TO INQUIRE INTO THE SEVERAL MATTERS RELATIVE TO COAL IN THE UNITED KINGDOM, July 27, 1871]