The Mining Folk Of Fife.

By David Rorie, M.D., D.P.H. Published as Appendix to "County Folklore. Example of printed Folklore Concerning Fife With Some additional Notes on Clackmannan & Kinross-shires. Collected by John Ewart Simpkins, 1914"

[For explanation of terms used on this page see the online Dictionary of the Scots Language]

All the folk-lore notes given here were gathered by me at first hand during a twelve years' residence in Fife, ten years of which were spent in the parish of Auchterderran, an agricultural and mining district. It is not pretended that all the customs, etc., mentioned were universal. Many of them were dying out, and many more were referred to jestingly, often with the semi-apologetic remarks, "that's an old freit, that's what the auld folk used to say, or do." But everything I have set down I have tested as having been at one time or another common in the district.

The Fifer, whether he deserves it or not, has the reputation of being more full of "freits " than the dweller in perhaps any other county in Scotland. He owes much to his isolated situation. The deep inlet of the Firth of Tay to the north, and the equally deep inlet of the Forth to the south, made communication with the outer world difficult and dangerous in these directions for many a long century. Eastwards the North Sea was an effective barrier, while going westward took the Fifer amongst the hills and the Highlanders. The genuine old-fashioned Fife miner has three great divisions of "incomers" of whom, when occasion arises, he speaks with contempt. These are -(i) Loudoners or natives of the Lothians, (2) Hielanters, who include all from Forfarshire to John o'Groats, and (3) Wast-Country Folk. And these last in his opinion, and not without reason, are perhaps the worst of all. Although present day facilities for travelling, and especially the Forth and Tay bridges, have done much to remove this clannishness amongst the folk, there is no doubt that here and there a considerable amount of it remains. Some time ago a man died in a Fifeshire mining village. He had been continuously resident there for twenty years, but he was not what the Fifer calls a "hereaboots" man - he was an "incomer." And so when he passed away the news went round the village that "the stranger" was dead.

When I went to Auchterderran in 1894 the great bulk of the mining population was composed of the old Fifeshire mining families, who were an industrious, intelligent, and markedly independent class. They worked in various small privately-owned mines, the proprietors of which in most cases had themselves sprung from the mining class, many of them being relatives of their employees; and a certain family feeling and friendship nearly always existed. With the advent of large Limited Liability Companies there was a corresponding extension of the workings, and a huge influx of a lower class of workman from the Lothians and the West country (involving an Irish element), while the small private concerns went inevitably to the wall.

Most of the old Fifeshire miners had dwelt for generations in the same hamlets, being born, brought up and married, and often dying in the same spot. Many of them were descendants of the old "adscripti glebae," the workers who were practically serfs, "thirled" to pit-work for life, and sold with the pit as it changed hands. It is strange to think that this extraordinary method of controlling labour prevailed in Scotland till 1775, so that an old miner of eighty years of age at the present day might quite well be the grandson of a man who had worked as a serf in the pit. During the earlier part of the nineteenth century the different hamlets naturally kept markedly to themselves. Within living memory all merchandise required for domestic use had to be purchased at the hamlet shop, usually kept by a relation of the colliery owner; any debts incurred to him being deducted from the men's wages. To keep such a shop was therefore a very safe speculation. There were other "off-takes," e.g. for medical attendance, pick-sharpening, etc.; and as wages ruled low the total sum received every fortnight on "pay-Saturday" was often small enough. The good type of miner always handed over his wages intact to his wife, who bought his tobacco for him along with her household purchases, and returned him a sum for pocket-money, usually spent on a "dram." An occasional excess in this line was not harshly judged, and good comradeship prevailed. An interesting comment was once made by an old Fifer after the influx into Auchterderran of "Loudoners" and "wast-country folk" occurred - "Ay, this is no' the place it used to be: ye canna lie fou' at the roadside noo wi'oot gettin' your pooches ripit!"

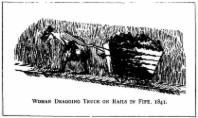

In the parish of Auchterderran the collieries in the days gone by were small, and only the more easily-got-at surface seams of coal were worked. The first seams to be worked out were those which cropped out to the surface, and the seam was simply followed in as far as it could be got at (an "ingaun e'e"), and when it got too deep for this method a shaft was driven. It was the custom for both man and wife to work in the pit. The man dug the coal and the woman (before winding machinery was introduced) carried it to the surface in her creel, either up the "in-gaun e'e" or up the side of the shaft by a circular ladder, as in the accompanying illustrations [click on images to view].

That this work of coal-bearing was coarse and degrading work for women, and that it attracted to it or caused to be forced into it the unfortunate and friendless, is shown by the following extract from "The Last Speech and dying Words of Margaret Millar, coal-bearer at Coldencleugh who was execute 10. February 1726 at the Gibbet of Dalkeith, for Murdering her own Child."

"The place of my birth was at Dysert in Fife. My Father John Millar was a Salter under my Lord Sinclar there, and I being in my Nonage left to the care of an Uncle, who put me to the Fostering, and after being wean'd from the Breast, was turn'd from Hand to Hand amongst other relations, when my Friends being wearied and neglecting me, I was obliged to engage with my Lord Sinclar's Coalliers to be a Bearer in his Lordship's Coalheughs; So being unaccustomed with that Yoke of Bondage, I endeavoured to make my Escape from such a World of Slavery, expecting to have made some better thereof: But in place of that I fell into a greater Snare."

Ventilation in the earlier part of last century was a negligible quantity, and the air was often too foul for the naked-light lamps to burn in. One old man, the husband of Mrs. H. mentioned later, told me that he remembered some sixty years ago working below ground by the phosphorescent light of decaying fish-heads, in a part of the mine where the air was too foul to allow his tallow lamp to burn. He said they gave enough light to show him where to "howk" his coal.

The following interesting account of mining life in bye-gone days was written in 1896 by an old miner, A.C., Lochgelly, then aged about seventy years :

"I will now give you my little essay on the rise and progress of the mining industry in Lochgelly for a hundred and fifty years back. You will find it both interesting and amusing, and at same time all truth. Their work and mode of living was the constant fire-side talk. We are the oldest race of miners that belongs to Lochgelly, and have been all born in that little old row of houses called Launcherhead, and the mines where they wrought were round about it. It was the custom at that time for the man and his wife to work both. The man digged the coals, and his wife carried them to the pit bank on her back. They were called Bearers, and if anything went wrong with the man she had to be both miner and Bearer both. Such was the case with my Grandmother. She was left a widow with five of a family, three girls and two boys. My Father was six months old, and my uncle B. was two years, there being no other way for her to support her family but to make herself a general miner. So she put her two boys in her coal creel, carried them down the pit and laid them at the stoop side until she digged her coals and carried them to the pit bank on her back. When she rested she gave my father a drink and my uncle a spoonful of cold stoved potatoes. Potatoes formed the greatest part of their living at that time. That was in about 1725 [Authors Footnote - Sic, but the date is obviously wrong. Probably it should be 1795]. There was only nine miners in Lochgelly at that time, and at the end of the year my grandmother had the highest out-put of coal on Lochgelly work. Their daily output was little over ten tons. Last time the mining industry of Lochgelly was brought up she was the leading character. After her family grew up she drove both coal mines and stone ones. She drove a great part of the day-level leading from Water Orr. The air was sometimes that bad that a light of no description would burn: the only light she had was the reflection from Fish Heads, and her family carried the rade to the bank [Authors Footnote – Fish Head- Cf. old H.'s description, Auchterderran : Rade = "Redd," refuse, material not coal]. The name of this remarkable female miner was Hannah Hodge. Sir Gilbert Elliot was the laird of Lochgelly at that time. He had them all up to Lochgelly House two or three [times] every year and had a proper spree with them. There was two Englishmen, father and son, the name of Chisholm, took Lochgelly work and keept it as long as they lived and their sons after them. They invented the first machine here for raising coal and that was a windlass and they raised the output from ten to fifteen tons. The only machine for raising coal before that was the miners' wives. As time rolled on the Father and Son got married on my two aunts. Such a marriage has not taken place in Lochgelly for one hundred and fifteen years (before that). William Stewart carried on the work after their father's death. They introduced a Gin and brought the output up to 25 tons. Mr. Henderson and company got the work next and they raised the output up to 30 tons. And it has increased every year since that time. When the Nellie workings got up through on the old workings that I heard them talk so much about I travelled (walked) a whole day to see where my Father and Mother wrought, and I saw my Uncle B.'s mind ('mind' = mine, Fifeshire) where he made such a narrow escape of his life. He was driving a mind from the parrot seam to the splent to let off a great quantity of water that was lying there. It blew the side out of his mind. It knocked him up to the high side which saved his life. If he had gone out the day level with the water he (had) never been seen (again). He was very jocular and about as good of walking on his hands as feet. He got himself rightly arranged with his lamp hanging on his backside and walked up and down past Launcherhead doors and every one that looked out thought they were no use of them going to work that day after seeing a man walking about the place wanting the head. All the miners in Lochgelly lived in Cooperhall and Launcherhead and was full of superstition." After dealing with Lochgelly in recent times the old man says : "For every holing a miner takes off he can sit down and say to himself 'I sit here where human foot has never trod nor human voice has rung’ and that is more than Stanley could say after his travels through Africa. "

Miners' Freits.

The old-fashioned miner had a strong objection to meeting a black cat or a woman, especially an "old wife," and more so one with a white mutch on, while on his way to work. Many colliers even yet will turn back and lose a day's work rather than proceed in face of the possible ill-luck involved. It is supposed to mean accident, either to the man or to the place he is in. The cases are cited of a man who, in spite of the meeting, went to work and got his leg broken, and of another who went to work and found his "place" fallen in.

When an accident happened in the pit, all who heard of it used to "lowse," i.e. cease from work. In these days of large collieries the news does not always reach the working places; but in the event of any serious accident, involving say, two or three deaths, the whole of the men employed usually come to the pit bank and cease work for the day.

The following are common freits noted at Auchterderran:

It is unlucky to begin work or start on a journey on a Friday.

It is unlucky to turn back after you have started out from the house.

It is unlucky to shake hands twice on saying good-bye.

It is unlucky to dream of eggs ; eggs mean "clashes " (evil-speaking : disputes).

To dream of rats is unlucky ; rats mean enemies.

To dream of a washing means a "flitting " (removal).

To dream of the loss of teeth means a death.

To dream of the loss of fingers means the same.

To rub the nose when you rise in the morning means that you will hear of a death before night.

It is unlucky to meet a woman with untidy shoes or stockings.

If a man's (or woman's) bootlace comes undone, his (or her) sweetheart (or wife or husband) is thinking of him (or her). (Evil wishing ties knots ; good wishing looses them.)

It is unlucky to put your shoes on the table, it will cause "strife." Ill luck can be averted by spitting on the soles.

If two people wash their hands together in a basin, the sign of the cross should be made in the water.

It is unlucky to go under a ladder.

It is unlucky to spill salt. If done some salt should be thrown over the left shoulder.

Breaking a mirror means ill-luck for seven years.

It is unlucky to give a present of a knife or scissors. It "cuts love."

Sudden silence means that an angel is passing through the room.

It is unlucky to look at the new moon through glass.

On first seeing the new moon you should turn a piece of silver in your pocket.

It is unlucky to give undue praise to horses, cattle, etc., or children. If this is done it constitutes " fore-speaking" and evil will follow. Hence probably the Scots invalid on being asked how he is says he "is no ony waur "—he avoids fore-speaking himself.

A cat will "suck" a child's breath and so cause death

A horse "sees things" invisible to the driver, "What are ye seein' noo ? " is a common remark when a horse shies without apparent cause.

It is lucky to have a horseshoe in the house.

A woman whose child had died, said to me : "This comes o' laughin' at freits." On enquiry I found that she had always condemned those who kept a horse-shoe at the fire-side (a common custom). She immediately procured one.

A pig sees the wind.

The "hole" in the forefoot of a pig is where the devils entered the Gadarene swine.

A man who has killed a lot of pigs in his day has a good chance of seeing the Devil.

It is unlucky to "harry" a swallow's nest.

If a swallow flies below your arm that arm will become paralysed.

Swallows or crows building near a house are lucky.

It is unlucky to have peacocks' feathers in the house.

Games

"Hainchin' the bool." A game played in the earlier half of the nineteenth century amongst the Fifeshire miners was called "hainchin' the bool." The "bool," which weighed about 4 Ibs., and was somewhat larger than a cricket ball, was chipped round from a piece of whin-stone with a specially made small iron hammer. The game was played on the high-road where a suitably level piece could be got. The ball was held in the hand, and the arm brought up sharply against the haunch, when the ball was let go. Experts are said to have been able to throw it over 200 yards. The game was ultimately stopped by the authorities. This form of throwing is very frequently practised by boys to throw stones over a river or out to sea from the beach. How long "hainchin' the bool" had been practised in Fife it is hard to say, but the stone ball was of the same type as the "prehistoric" stone-balls fairly common in Scotland, some of which at least may have been used for a similar purpose.

"Shinty " formerly took the place of the present-day universally popular football.

"The dulls" or "Dully" (Rounders) was also formerly popular.

Cock-fighting was formerly very common amongst the Fife-shire miners. Even yet, in spite of legal repression, many gamecocks are bred and matches held on the quiet. A disused quarry-in the parish (Auchterderran) was a favourite amphitheatre for large matches (e.g. an inter-parish or inter-county combat), and Sunday a favourite day. Quite a large crowd of men would collect, often driving long distances, to view the combat. In Fife the cocks were always fought with the natural spur.

Quoits is an old game still played with great interest and skill.

MARRIAGE

"Marry for love and wark for siller" runs the Fife proverb, setting forth the principles on which matrimony should be undertaken.

On hearing of an intended marriage, the customary enquiry is, as to the man, "Wha's he takkin’ ?" but in the case of a woman, "Wha's she gettin' ?" Other common sayings are: "She's ower mony werrocks (bunions) to get a man ": and, "Mim-mou'ed maidens never get a man ; muckle-mou'ed maids get twa." "When ye tak' a man, ye tak' a maister," is a woman's proverb. But when once the wedding-ring was on, it was unlucky to take it off again. "Loss the ring, loss the man."

"Change the name and no’ the letter,

Change for the waur and no’ the better."

It was quite common in the parish for a married woman to be referred to by her maiden name in preference to the surname she was entitled to use by marriage.

The following account of old-time marriage customs among the mining folk was taken down in 1903 from the description of Mrs. H., of Auchterderran, aged seventy-five. She had been born, brought up, and had lived all her life, in one hamlet in the parish, and had never been further than ten miles away from it.

When the "coortin' " had been successfully accomplished, the custom was to celebrate "the Contrack night." This was the night that "the cries" had been given in (i.e. the notification to the minister to proclaim the banns of marriage) and a convivial meeting was held in the house of the bride. The food was plain (perhaps "dried fish and tatties"), and there was much innocent merriment; one outstanding part of the programme being the "feet-washing," of the bridegroom. This performance varied in severity from plain water and soap to a mixture of black lead, treacle, etc., and the victim always struggled against the attentions of the operators. In spite of his efforts at self-defence the process was always very thoroughly carried out. As regards the "cries," the proper thing was to be "cried " three Sundays running, for which the fee was 5s. But if you hurried matters up, and were cried twice, you had to pay 75. 6d., while if your haste was more extreme and you were only cried once, you were mulcted in the sum of 10s. 6d.

The marriage usually took place in church. On the marriage-day the bridegroom and bride with best-man and bridesmaids set out in procession for the Kirk, the bride and groom sometimes being "bowered," i.e. having an arch of green boughs held over their heads. All the couples went "traivlin' linkit" (walking arm in arm) sometimes to the number of thirty-two couples, while guns and pistols were fired on the march, and all sorts of noise and joking kept up. In the parish of Auchterderran it was the rule (owing to damage having been done on one occasion to the sacred edifice), that all this had to cease when the procession came in sight of the kirk at the top of Bowhill Brae, about two hundred yards from the building. Money was dispensed by the bridegroom, which was called the "ba' siller." All this is done away with now, with the exception of the ba' siller, which is always looked for.

On returning home, the bride had a cake of shortbread broken over her head while crossing the threshold. This is still sometimes done. In the evening a dance would be held and "the green-garters" (which had been knitted in anticipation by the best maid) were pinned surreptitiously on to the clothing of the elder unmarried brother or sister of the bride. When discovered they were removed and tied round the left arm and worn for the rest of the evening. The green garters are still in evidence. The unmarried women present would be told to rub against the bride "for luck" as that would ensure their own early marriage. The proceedings terminated with the "beddin' o' the bride." When the bride got into bed her left leg stocking was taken off and she had to throw it over her shoulder, when it was fought for by those in the room, the one who secured it being held as safe to be married next. The bride had to sit up in bed until the bridegroom came and "laid her doon." Sometimes the roughest of horseplay went on. In one case mentioned by an old resident in the parish, practically "a' the company " got on to the bed, which broke and fell on the ground.

"The Kirkin' " took place the following Sunday, when three couples sat in one seat; viz. the bride and bridegroom, the best maid and best man, and "anither lad and his lass. "

On the first appearance of the newly-married man at his work he had to "pay aff" or "stand his hand," (stand treat). Failing this he was rubbed all over with dust and grime. This was called "creelin."

This "creelin' " is a very attenuated survival of the custom mentioned by Allan Ramsay in his second supplemental canto to "Christ's Kirk on the Green," where the day after the marriage the bridegroom has "for merriment, a creel or basket bound, full of stones, upon his back ; and, if he has acted a manly part, his young wife with all imaginable speed cuts the cords, and relieves him of his burden." [The Works of Allan Ramsay, vol. i. p.328. A. Fullarton & Co., London, Edinburgh, and Dublin. 1851]

"The bride was now laid in her bed,

Her left leg ho' was flung,

And Geordie Gib was fidging glad,

Because it hit Jean Gunn."

ALLAN RAMSAY, first supplemental canto to "Christ's Kirk on the Green

". . . The bride she made a fen',

To sit in wylicoat sae braw, upon her nether en'." Idem.

BIRTH AND INFANCY.

Of the three stages of life round which old customs and beliefs cluster,—namely, marriage, birth, and death,—the second has perhaps the greatest amount of folklore connected with it. Some part of what is here set down has already appeared in the Caledonian Medical Journal, vol. v., [The Scottish Bone-setter, The Obstetric Folk-Lore of Fife, and Popular Pathology; also " Some Fifeshire Folk-Medicine " in the Edinburgh Medical Journal, 1904.] but all of it is the fruit of many years' personal experience as a medical practitioner among the folk of Fife, more especially among those who daily go down into the coalpits of the county to earn their bread.

Pregnancy.

There is a popular belief that when pregnancy commences the husband is afflicted with toothache or some other minor ailment, and that he is liable to this complaint until the birth of the child. On one occasion a man came to me to have a troublesome molar extracted. When the operation was over he remarked, in all earnestness, "I'm feared she's bye wi' it again, doctor. That tooth's been yarkin' awa' the last fourteen days, an it's aye been the way wi' me a' the time she's carryin' them." Another patient assured me that her husband "aye bred alang wi' her" and that it was the persistence of toothache in her adult unmarried son which led her to the (correct) suspicion that he had broken the seventh commandment, and made her a grandmother.

Pregnancy is frequently dated from taking a "scunner" (disgust) at certain articles of food—tea, fish, etc. If the confinement is misdated, the woman whose calculations have gone wrong is said to "have lost her nick-stick," a reference to the old-fashioned tally.

While the woman is pregnant she must not sit with one leg crossed over the other, as she may thereby cause a cross-birth ; nor, for the same reason, may she sit with folded arms. If she is much troubled with heartburn, her future offspring will have a good head of hair; while a dietary including too much oatmeal will cause trouble to those washing the child, as it produces a copious coating of vernix caseosa.

Many mothers believe that the tastes (likes and dislikes) of the child are dependent on the mother's diet while pregnant; e.g. a woman who has eaten much syrup will have a syrup-loving child. If a woman while pregnant has been "greenin' " (longing for) any article of diet which has been denied to her, the child when born will keep shooting out its tongue until its lips have been touched with the article in question.

The belief in maternal impressions is of course fixed and certain ; and wonderful are the tales told of children born with a "snap" on the cheek (through that favourite piece of confectionery having been playfully thrown at the mother), or with a mouse on the leg. E.g. a woman who was slapped in the face with a red handkerchief while pregnant, had a child with a red mark on the forehead ; another woman had a "red hand " on her own abdomen because, before her birth, her mother's nightgown caught fire, and she laid her hand violently on her body to extinguish the flames.

It is always considered among the folk a most reprehensible thing to throw anything, even in jest, at a pregnant woman, on account of thereby causing a birthmark, or even a marked deformity, to the future offspring. Should something be thrown, however, and the part hit be an uncovered part of the body, such as the face, neck, or hand, the probable birthmark may be transferred to a part covered with clothes, if the woman touches with her hand the spot where she has been struck, and then touches a clothed part of her person. A young married woman is always so advised by her elders. The transference is only effectual before the fourth month of pregnancy. Any start or fright to a pregnant woman is considered dangerous as the child may "put up its hand and grip the mother's heart." I have heard sudden deaths in pregnancy attributed to this. Each pregnancy is supposed to cost the woman a tooth.

A barren woman is often told chaffingly to "tak' a rub " Against a pregnant woman and "get some o' her luck."

If a woman is presented with a bunch of lilies before her child's birth, the child will be a girl. This is believed to be of French origin, as it was narrated by a daughter of a Frenchman who was taken prisoner at Waterloo. She lived in Ceres, Fife.

Children (generally illegitimate) "gotten oot o' doors" were expected to be boys. "It couldna but be a laddie, it was gotten amang the green girss (grass)"; (cf. "The Birth of Robin Hood," in Jamieson's Popular Ballads, 1806).

Childbed.

When labour was in progress, various proverbs, consolatory and otherwise, were always used ; such as, "Ye'll be waur afore ye're better" ; "The hetter war, the suner peace" ; "Ye dinna ken ye're livin' yet," etc.

In a prolonged or tedious labour an older woman would often open the door and leave it slightly ajar.

It was not uncommon for some women to desire to be confined kneeling in front of a chair, on the ground that "a’ their bairns had come hame that way." This position must have been very common at one time.

The placenta was usually burned, sometimes buried.

After the birth the mother had to be very careful till the "ninth day" was past. Till then, she was not allowed to "redd" her hair, or to "lift her hands" abune the breath, " i.e. higher than her mouth. Nor, if she "tak' a grewsin'," (rigor), must she touch her mammae, or a "beelin' " (suppurating) breast will be the consequence. "I maun ha' gruppit it," is often given as the cause of an abscess. And if, while "grewsin' " she were to grip her child, it would take the illness which caused the rigor.

"Nurse weel the first year, ye'll no nurse twa," was the advice given by experienced elders to young mothers.

"A woman was in seeing a neighbour who had had a 'little body.' The patient got up while the caller was in. The caller was going out again, but she was brought back until the mother got into bed again. Before leaving, the caller got 'the fitale dram.' " (Cowdenbeath).

The Newborn Infant.

When the child was born, it was frequently greeted with the words, "Ye've come into a cauld warl' noo."

The child may be born with a caul ("coolie," "happie-hoo," "sillie-hoo," or "hallie-hoo") over its face. This is a sign of good luck, and is still frequently preserved. I was once shown a specimen fifty years old, by its owner, who as it happens has been a peculiarly unfortunate woman. Some held that if given to a friend the caul will serve as a barometer of the donor's health. If in good health, it keeps dry, but if the giver turns ill, the hood becomes moist.

A child born feet first was held to be either possessed of the gift of second sight, or to be born "a wanderer in foreign countries."

A premature child will live if born at the seventh month, but not if born at the eighth.

If the child's first cry can be twisted into "dey" (father), the next comer will be a male.

The umbilical cord must be cut short in the case of a girl, but the boy whose umbilical cord is cut too short will, when his time comes, run the risk of either being a childless man, or a bed-wetter.

The child at birth used in the old days to be wrapped, if a male, in the mother's petticoat; if a female, in the father's shirt. If this was not done the child was thought to run the risk either of not being married at all, or if married, of being childless.

If the child micturates freely at birth, it is considered a sign of good luck to it and to all who may participate in the benefit.

The nurse examines the child to see that it is "wice and warl' like," and that there are no signs of its being an "objeck," or a "natural" Should the child have "hare-shaw" (hare-lip), or "whummle-bore" (cleft-palate), there will naturally be much chagrin, but a "bramble-mark" or "rasp" (naevus) is not objected to—unless on the face—as it is supposed to indicate future wealth. Such marks are held to increase in size and darken in colour as the fruits in question ripen, and to become more marked and prominent on the child's birthday. A child with two whorls on its head will be a wanderer, or, otherwise, will live to see two monarchs crowned.

It occasionally happens that a child is born with one or more of its teeth cut. This is considered very lucky ; but the teeth should be "howkit out" (dug out) to avoid disheartening the mother, for "sune teeth, sune anither. "

If the child is pronounced to be like father or mother, some one present will say, "Weel, it couldna be like a nearer freen'!" It is held that the child will be liker the parent who has either been fonder of the other at the time it was begotten, or fonder of the other during the pregnancy, " because he or she looks often at, and thinks often o' " the other. Or again, that the infant will be more like the parent who has the stronger constitution.

If the little stranger is a well-developed child, we are told : “That ane hasna been fed on deaf nuts” (Deaf nuts are worthless withered nuts.) Should it have enlarged breasts, the common and dangerous practice of "milking the breasts" is almost always resorted to in the case of a girl; but if a boy were so treated, it is thought that it would injure his chance of becoming a father hereafter.

It is considered very unlucky to weigh a newly-born child, and very genuine opposition may be offered to the proposal.

To wash the child's "loof" (palm) too thoroughly is held to spoil its chance of "gainin' gear," while to wash its back too well for the first three weeks is thought to weaken it. Others say the child's hands and arms should not be washed " till it is a gude twa-three weeks auld, as it taks their luck awa." (Cowdenbeath)

Mrs H. of Auchterderran, previously mentioned, said that "when she was a lassie" the howdie in charge would then mould and press the child's head ("straik it") to " pit it in til shape," special attention being paid to the nose. A mouthful of whisky was taken, and skilfully blown as a spray over the child's head, and then massaged in "to strengthen the heid." A plain closely-fitting cap ("under-mutchie") was then applied, and a more ornamental one on the top of that, as the child was supposed to take cold very readily through the "openins o' the heid" (fontanelles), by which " theair would get into the brain."

If a child cries continuously after being dressed at birth, the granny or some other wise elder will say, "If this gangs on we'll ha'e to pit on the girdle" (the large circular flat baking-iron on which scones and oatcakes are "fired"). Sometimes this is actually done, but the practice is rare now, and very few can give the true meaning of the saying. The idea is that the crying child is a changeling, and that if held over the fire it will go up the chimney, while the girdle will save the real child's feet from being burnt as it comes down to take its own legitimate place.

First Ceremonies.

The ceremony of drinking the child's health at birth ("wettin' the bairn's heid") is laid stress on, and those not "drinkin' oot the dram" are expostulated with thus: "Ye wouldna tak' awa' the bairn's beauty ? (or luck)." The refreshments, usually shortbread and whisky, are called " the bairn's cakes."

A visitor going to see a newborn child must not go empty-handed but must carry some small gift for presentation to the youngster, or he or she will carry away the child's beauty.

The child should always, when possible, be carried upstairs before it is carried down ; and where this is impossible, a box or chair will give the necessary rise in life.

"The bairn's piece” was a piece of cake, or bread and cheese, or biscuit, wrapped in a handkerchief and carried by the woman who was taking the child to the kirk for the christening. This woman was always if possible one of good repute in the district, and the office was considered an honour. "Mony an ane I carried to the kirk," said old Mrs. H., with pride. The first person met with on the way, whether "kent face" or stranger, was presented with "the bairn's piece," and was expected to partake of the proffered refreshment. Sometimes he or she would indulge in prophecy and say, "A lassie the next time," or, "a laddie" ; but failing this it was considered that if the person met was a male, the mother's next child would be a female, and vice versa. The custom is now practically extinct, even in country places.

"Children that are taken to be christened are taken in at the little gate instead of at the big gate now, since suicides are not taken over the church wall to be buried, as it was supposed that the first child that was taken in at the gate would commit suicide." (Verbatim as given. Cowdenbeath. Cf. p. 174.)

If on a Sunday a boy and a girl are being christened, the girl must be christened before the boy, otherwise she will have a beard.

On the child's first visit to another house its mouth is filled with sugar "for luck." Unless this was done the bairn would always be licking its lips and shooting out its tongue, and be generally discontented. The first visit of an infant to another house brings luck to that house, provided it is not carried by its mother, but if the mother herself is carrying the child, it is not every neighbour that would welcome the visit.

"The first time you take out your first baby, you should not bring it in yourself. Go in yourself first and get some other one to bring it in ; or come in backwards with it." (Cowdenbeath.)

The Cradle.

Various beliefs are connected with the cradle The first child should not be rocked in a new cradle, but in a borrowed old one ; nor should the cradle be in the house before the child is born. In sending the borrowed cradle back, it should never be sent empty, but with a blanket or pillow in it, nor should it touch the ground on the journey. Even when the child is older and the mother wishes to take the cradle to a neighbour's house for a "crack," it is unlucky to take it in empty. A pillow or blanket should be in it, or better still, the child should be placed in the cradle and carried in that way. An empty cradle should never be rocked, as it gives the child "a sair weim."

If a mother thinks she is not to have more children, and so gives her cradle away, another child will be born to her.

Early Infancy.

A child with differently coloured eyes (e.g. one blue, one brown) will never live to grow up.

If a young child on being given a piece of money, holds it tight, it will turn out "awfu' grippy" (greedy) ; but if the money slips through its fingers it will be openhanded and generous.

If the child "neezes" (sneezes), the correct thing is to say, "Bless the bairn !" If it "gants" (yawns), the chin is carefully pushed up to close the mouth.

When the child's nails require shortening, they should not be cut with scissors, but bitten. If a child's nails are cut before it is a year old (some say six months), it will be "tarry-fingered," (a thief).

A child speaking before six months old will, if a boy, not live to comb a grey head.

A child speaking before walking will turn out "an awfu' leear."

The first time a child creeps, if it makes for the door, it will creep through life and be a slowcoach, and never "mak' a name for itsel'."

If a child on first trying to walk is inclined to run, it will have more failures than successes in life.

A child should not see itself in a mirror before it gets its teeth, as it will not live to be five years old

Gums through which the teeth are shining are called "breedin' gums," and should be rubbed with a silver thimble or a shilling to bring the teeth through. If a stranger (i.e. any other than the mother) discovers the first tooth, the mother has to give that person a present. (Auchterderran.)

Early teething portends sundry troubles. "Teeth sune gotten, teeth sune lost" ; "Sune teeth, sune sorrow." And as regards the mother: "Sune teeth, sune anither"; or, "Sune teeth, sune mair."

To cut the upper teeth before the lower is very unlucky, for

"He that cuts his teeth abune

Will never wear his marriage shoon."

When a milk-tooth comes out, it should be put in the fire with a little salt, and either of the following verses repeated :

"Fire, fire, burn bane,

God gi' me my teeth again."

Or,

"Burn, burn, blue tooth,

Come again a new tooth.

Families.

An addition to a miner's family, if a boy, is described as "a tub o' great" ; if a girl, as "a tub o' sma'."

A family of two is described as "a doo's cleckin' " (i.e. a pigeon's hatch).

A family of three is looked on as ideal: "twa to fecht an' ane to sinder " (separate). Sometimes another child is allowed, and it becomes "twa to fecht, ane to sinder, an' ane to rin an' tell."

The last of the family is described as "the shakkins o' the poke," (bag). "Losh, wumman ! this'il surely be the shakkins o' the poke noo ! "

LEECHCRAFT.

"Folk-medicine," says Sir Clifford Allbutt (Brit. Med. Journal, Nov. 20, 1909), "whether independent or still engaged with religion and custom, belongs to all peoples and all times, including our own. It is not the appanage of a nation ; it is rooted in man, in his needs and in his primeval observation, instinct, reason and temperament. . . . To Folk-medicine doubt is unknown ; it brings the peace of security.

The Leech.

In folk-surgery, the bone-setter holds an accepted position. "A' body kens doctors ken naething aboot banes." It is a matter of "heirskep" (heredity). The bone-setter's father before him, or at least his grandfather, or at the very worst his aunt, possessed "the touch," as it is called, in their day and generation. "It rins in the bluid."

I know not why, but this particular unqualified practitioner is most frequently a blacksmith. Still, among the many Fifeshire bone-setters I have known or heard of were a schoolmaster, a quarryman, a platelayer, a midwife, and a joiner.

A rough and ready massage plays an important part in the modus operandi ; so does the implicit faith of the patient. The fearlessness of utter ignorance leads them to deal with adhesions in joints in the most thorough-going fashion, and we hear of their successes—not their failures. Many of them have the gift—a gift also common to others who never use it as hereditary skill — of making a cracking noise at the thumb or finger joint by flexion and extension. When an injury is shown for treatment, the bone-setter handles it freely, says how many bones are "out" and then works away at the joint, making cracking noises with his own fingers, each separate noise representing one of the patient's bones returning to its proper position. "They maun ha' been oot," says the sufferer afterwards : "I heard them gaun in." A coachman who had been flung off his box and got a bruised elbow had thirteen small bones "put in " by one famous blacksmith still in practice.

I suppose every medical practitioner in Fife could tell of cases ruined by these charlatans. On one occasion I was asked to see a ploughman who had fallen off a cart. I found him with a Colles' fracture, the injured part covered with a stinking greasy rag, above which were firmly whipped two leather bootlaces. The bones were not in position, and the hand, from interference with the circulation, was in a fair way to become gangrenous. Yet the injury had been met with a week previously, and both he and his employer had been highly pleased with the treatment of the "bone-doctor" who had been consulted. I was only wanted to fill in the insurance schedule.

One curious qualification for bone-setting was given me by a collier who had been to a bone-setter with a "staved thoomb." I asked him why he had gone there. "Lord, man ! I dinna ken. They say he's unco skeely." But what training had he ? " Weel, he was aince in a farm, and drank himsel' oot o't! "

Popular Physiological Ideas.

It is believed that there is "a change in the system" every seven years.

Hair. If a grey hair is pulled out three will come in its place. (Auchterderran and Fife generally.)

A horsehair put into water is supposed to turn into a worm or an eel. Many people otherwise intelligent fully believe this. (Auchterderran and Fife generally.)

Hair and nails should not be cut on Sunday. "Cursed is he that cuts hair or horn on the Sabbath," was quoted against a resident who had dishorned a "cattle-beast" on Sunday. (Auchterderran.)

An excessive amount of hair on a new-born child's head is an explanation of the mother having suffered from heartburn.

"A hairy man's a happy man—or, a ' geary' (wealthy) man"; —a hairy wife's a witch."

A tuft of hair on the head that will not keep down when brushed is called "a coo's lick."

Red Hair. A red-haired first-foot is very unlucky. "He's waur than daft, he's reid-heided." There is a schoolboy rhyme :

"Reid held, curly pow, Pish on the grass and gar it grow."

Large Head. "Big heid, little writ."

The Heart. "To gar the heart rise," to cause nausea.

"To get roond the heart," to cause faintness. (" It fairly got roond my heart."

Sudden death is explained as due to the heart having been "ca'ed (pushed) aff its stalk,"

Any injury, however slight, near the heart, is looked upon as dangerous. "Far frae the heart" is used to mean, not dangerous, not of much importance, trifling. "O that's far frae the heart! " not worth bothering about.

"Whole at the heart," courageous, in good spirits. "But a' the time he lay he was whole at the heart."

"Something cam' ower the heart," t.e. a feeling of faintness occurred.

"I saw her heart fill," I saw she was overcome with emotion.

Hiccough is supposed to be caused by "a nerve in the heart," and at every hiccough " a drop o' blude leaves the heart."

Jugular vein. Great importance is attached to any injury "near the joogler." Fear will be expressed lest any swelling in the neck should be "pressin' on the joogler."

Menstruation. It is steadfastly believed by the folk that substances such as jam, preserves, or pickles, made by a menstruating woman will not keep, but will for a certainty go bad. On one occasion I was told in all seriousness that a newly-killed pig had been rendered quite unfit for food through being handled by a woman "in her courses," all curing processes being useless to check the rapid decomposition that followed.

Nerves. A "nervish " person is a nervous person : a " nervey " one, a quick active person.

Hysteria is described as "the nerves gaun through the body."

A highly neurotic imaginative person is described as "a heap o' nerves"- "a mass o' nerves."

A pot-bellied individual is described as "cob-weimed." The "cob" is the grub found at the root of the docken, and is a favourite bait with fishers.

Sneezing ("neezing") is held to clear the brain.

Spittle, spitting. Fasting spittle is a cure for warts and for sore eyes.

The spittle of a dog ("dog's lick") is a cure for cuts and burns

Spitting for luck. At the conclusion of a bargain the money is spat on "for luck." Money received in charity from one for whom the recipient has a regard is similarly treated.

A man meeting a friend whom he has not seen for a long time will spit on his hand before extending it for shaking hands.

Along the coast, any dead carcass is spat on with the formula, "That's no my granny."

A schoolboy challenge is to extend the right hand and ask another boy to " spit owre that." If he does so, the fight begins. A scholboy saying (contemptuous) : "I'll spit in your e'e an' choke ye."

Teeth. Toothache is caused by "a worm in the teeth."

To extract eye-teeth endangers the sight.

"He's cut a' his teeth," he is wide awake.

"He didna cut his teeth yesterday," he is an experienced person.

"A toothful," a small quantity of anything.

Thumb. An injury to the thumb is supposed to be specially apt to cause lock-jaw.

Tongue. "Tongue-tackit," tongue-tied.

"The little tongue," the uvula.

If a magpie's tongue has a piece "nickit oot " between two silver sixpences, the bird will be able to speak.

A seton passed in below the tongue of a dog will make it quiet while hunting. A poacher's dodge.

"To have a dirty tongue," to be a foul speaker.

"To gie the rough side o' the tongue," to swear at, to speak harshly.

"Her tongue rins ower fast," or "She's ower fast wi' her tongue," said of women.

Unconsciousness is described as "deid to the warl'." "I was deid to the warl for sax hoors."

Wind (flatulence) has extraordinary powers attributed to it : "gettin' roon' the heart," "gaun to the heid." An acute pain in the chest or belly is often said to be caused by "the wind gettin' in atween the fell (skin) and the flesh.

Yawning (" gantin' "). There is a proverbial saying :

"They never gantit, But wantit

Meat, meal, or makkin' o' " (fondling, petting).

Pathological Ideas.

There is always, for example, a fear of taking anything that may "leed the tribble." A light is going on between the trouble and the " system," and unsuitable medicine may go to help the former at the expense of the latter. "For ony favour," said one woman, " dinna gie me ony thing that will gar me eat, for a' I tak just gangs to the hoast and strengthens it." Again, in the case of a poultice, there is an underlying idea of the transference of the "tribble" from the afflicted body to the poultice, and it is with this idea that the poultice is usually burnt. The poultice is held to "draw the tribble" : the disease is "in" until it has been extracted : it has to be got out. Some poultices, such as carrot or soap-and-sugar poultices, are described as "awfu' drawin' things." "Is it no' drawin' it owre sair ? " is a common query regarding a poultice or a dressing. When a blister does not rise readily it is looked on as a bad sign : the trouble cannot be drawn out: "it is ill to draw," - "dour to draw" - "the tribble's deep in."

Disease may also be "drawn out" from a human body to that of a lower animal, as appears from the treatment of syphilis noted below and other cases.

Contagion.

Boils are looked upon as a sign of rude health. Swollen glands (referred to as "waxen kernels" or "cruels") are looked on as a sign of the system being "down."

Cancer is referred to as "eatin' cancer." A common expression is "They say an eatin' cancer will eat a loaf." Of one case of cancer of the breast a woman said, "It used to eat half a loaf o' bread and a gill o' whisky in twa days " (Auchterderran).

Celibacy in a male is held to be bad for mental conditions. "His maidenheid's gaun to his brain" : said scoffingly of an eccentric single man.

Delirium. A delirious person is spoken of as "carried" One who is excited is spoken of as "raised" or "in a raptur'," and a confused person as "ravelled" (i.e. tangled - a ravelled skein of wool is a tangled skein).

Drunkenness. A drunk man, if very drunk, is described as "mortagious," "miracklous," " steamin’ wi’ drink" or "blin' fou'." A chronic drunkard (" drooth") is spoken of as "a sand-bed o' drink." A man wanting a drink will ask you to " stan’ your hand" or ask "Hae ye ony gude in your mind?" or "Can ye save a life? " (Auchterderran).

Hives. Jamieson in his dictionary gives this word as meaning "any eruption on the skin when the disorder is supposed to proceed from an internal cause. Thus bowel-hive is the name given to a disease in children in which the groin is said to swell. Hives is used to denote both the red and yellow gum (Lothians) A.S. Heafian, to swell" But this is by no means a complete definition for Hives in Fife. Generally speaking, if an infant is at all out of sorts it is said to be hivie : diarrhoea, vomiting, thrush—all these conditions come under the adjective, while a fatal result is frequent through "the hives gaun roond the heart." The commonest varieties of hives, so far as we can classify them, are those that follow :

1. Bowel-hives is the diarrhoea so often associated with dentition and mal-feeding in infants.

2. Oot-fleein' hives is where we get a rash of any sort (short of the exanthemata). For example, eczema capitis is frequently described as starting with "a hive " on the brow, and the suda-mina so common on neck and nose in the first few days of infant life are frequently looked on as a good sign, and called "the thrivin' hives."

3. In-fleein' hives is - what ? It frequently spells sudden death, or, at any rate, sudden death is quite satisfactorily accounted for by the fact that "the hives have gone in wan" (inwards), the usual goal being, as I have mentioned, the heart.

4. The bannock-hive is a term applied humorously and contemptuously to the person who is suffering from a gastric derangement as a result of over-eating. When doubt is thrown in the family circle on a member's claim to be an invalid, we hear the phrase, "Weel, if ye're hivie, it's the bannock-hive " ; similar to "Ye're meat-heal, ony way," or to Gait's famous " Ony sma' haud o' health he has is aye at meal-times."

Mumps. Local terms for this are "Bumps," "Buffets," and "Branks " - "Branks " meaning the halter for a cow (Auchterderran).

Pap o' the hass ("hawse," "hass " - throat, "pap o' the hass " —uvula). In relaxed throat the condition is referred to as "the pap o' the hass being down." It is believed that there is one single hair in the head, which, if found and pulled, will "bring the pap o' the hass up." The difficulty is, of course, to find it.

Suicide. It is often said of a suicide "he maun hae been gey sair left to himsel' afore he did that."

White liver. A man who has been a widower several times ("wearin' " his third or fourth wife) is supposed to have a "white liver," along with which condition goes a "bad breath" fatal to the spouse.

Health Maxims.

Better wear shoon than sheets.

Feed a cold and starve a fever

If ye want to be sune weel, be lang sick : i.e. keep your bed till you are better.

"He's meat-heal ony way," is said of an invalid whose illness is not believed in.

Nervous people are said to be "feared o' the death they'll never dee."

"He'll no kill," and " He has a gey teuch sinon (sinew) in his neck," are said of hardy persons.

"Let the sau sink to the sair," was said jestingly as a reason for drinking whisky instead of rubbing it in as an outward application.

Hygiene and General Treatment.

Skin eruptions are often explained as "just the time o' year." Boils, pimples, rashes, etc., are held often to come out in the spring.

Spring Medicine. In springtime there is a necessity "to clear the system ; " which is best done by a purge and a vomit. A well at Balgreggie, Auchterderran (mentioned in Sibbald's Fife), was once resorted to for this. This well has now fallen in, and is simply a marshy spot.

Sulphur and cream of tartar is a favourite spring drink.

Water. On coming to another place, the "cheenge o' water" is held to cause boils, pimples, and other skin eruptions.

Living too near water causes decay in the teeth.

It is dangerous to give cold water as a drink in fevers and feverish conditions, or in the puerperium.

It is held that "measles should not be wet," and this is often a valid excuse for keeping the patient lamentably dirty.

Too much washing is weakening. The old-fashioned Fife miner objects, on this account, to wet his knees and back.

A pail of water should not be left standing exposed to the sun, as the sun "withers" it.

Air. The smell of a stable or byre is wholesome for children and invalids. Change of air is advantageous in whooping-cough. (The length of time the change lasts is of no moment.) On one occasion a miner took his child down the pit into the draught of an air-course for change of air. It died of pneumonia two days later. In some cases men have been known to take more bread with them for their "pit-piece" than they needed, and the surplus bread, which had received the change of air, was given to the patient.

Earth. Breathing the smell of freshly-dug earth was held to be good for whooping-cough, and also for those who had been poisoned with bad air. A hole was dug in the ground and the patient "breathed the air off it." A "divot " of turf was sometimes in the old days cut and placed on the pillow.

Blue flannel is held to be "a rale healin' thing" when applied to bruises, sore backs, etc. The working shirt of the Fifeshire miner is always of blue flannel.

Ointment. Butter wrapped in linen and buried in the ground until it becomes curdy is held to be a fine natural "sau" (salve) for any broken surface.

Diseases and Remedies.

Burns. Holding the burnt part near the fire "draws oot the heat" from the burn

"The drinking diabetes." In 1904 a child suffering from "diabetes" was directed by a "tinkler wife" to eat a "saut herrin'." After it had done this, the child's arms were tied behind its back and it was held over running water. A "beast" (which had been the cause of the trouble), rendered very thirsty by the meal of salt herring and hearing the sound of water, came up the child's throat, and the child recovered. (Cf. Worms, infra.)

"Fire" (any foreign body, metallic), in the eye, is removed (short of working at it with a penknife) by the operator (1) licking the eye with his tongue : (2) drawing the sleeve of his flannel shirt across the eyeball: or (3) by passing a looped horsehair below the lid.

Headache. A handkerchief (preferably a red handkerchief) tied tightly round the head is good for headache.

Hydrophobia was treated in the old days by smothering the patient between two feather beds. A house in Auchterderran was pointed out where this is said to have been done.

Inflamed eyes are cured by wearing earrings : by application of fasting spittle ; by the application of mother's milk; and by cow's milk and water used as a lotion

Piles, treated by (1) sitting over a pail containing smouldering burnt leather ; (2) the application of used axle-grease.

Rheumatism ("Pains") is treated by (1) switching the affected parts with freshly-gathered nettles; (2) carrying a potato in the pocket; (3) supping turpentine and sugar, or (4) sulphur and treacle; (5) wearing flowers of sulphur in the stockings, or rubbed into blue flannel; (6) by inunction of bullock's marrow twice boiled ; (7) rubbing in "oil o' saut" or "fore-shot."

Ringworm is treated with (1) ink; (2) gunpowder and salt butter ; (3) sulphur and butter ; (4) rubbing with a gold ring.

Toothache is caused by a worm in the tooth, and is cured in women by smoking (Auchterderran). It may also be cured by snuffing salt up the nose (a fisher cure, St. Andrews), or by keeping a mouthful of paraffin oil in the mouth (Auchterderran). A contemptuous cure advised to a voluble sufferer is, "Fill your mouth wi' watter and sit on the fire till it boils."

Warts. Cures : (1) rubbing with a slug and impaling the slug on a thorn. As the slug decays the warts go ; (2) rubbing with a piece of stolen meat, as the meat decays the warts go ; (3) tying as many knots on a piece of string as there are warts, and burying the string, as the string decays the warts go ; (4) take a piece of straw and cut it into as many pieces as there are warts, cither bury them or strew them to the winds; (5) dip the warts into the water-tub where the smith cools the red-hot horse-shoes in the smithy ; (6) dip the warts in pig's blood when the pig is killed. Blood from a wart is held to cause more.

Whooping-cough. Besides the cures for this mentioned above, there are the following. (1) Passing the child under the belly of a donkey. (2) Carrying the child until you meet a rider on a white (or a piebald) horse, and asking his advice : what he advised had to be done (3) Taking the child to a lime-kiln. (4) Taking the child to a gas-works. During an outbreak of whooping-cough in 1891, the children of the man in charge of, and living at, a gas works did not take the complaint. As a matter of fact, the air in and near a gas-works contains pyridin, which acts as an antiseptic and a germicide. (5) Treating the child with roasted mouse-dust. (6) Getting bread and milk from a woman whose married surname was the same as her maiden one. (7) Giving the patient a sudden start.

Worms. Medicine for worms had to be given at the "heicht o' the moon." The worms are held to "come oot " then. Another method was to make the sufferer chew bread, then spit it out and drink some whisky. The theory is that the worms smell the bread, open their mouths, and are then subsequently choked by the whisky ! (cf. Diabetes, above.)

Materia Medica.

1. Animal Cures.

Cattle. I have seen cow-dung used as a poultice for eczema of the scalp, for "foul-shave," and for suppuration (abscess in axilla). The general belief among "skeely wives" is that a cow-dung poultice is the "strongest-drawin' poultice" one can get.

Cow's milk mixed with water is used as an eye-lotion.

The marrow of bullock's bones, twice boiled, is used as an inunction in rheumatism.

One often hears of an ox having been killed and split up "in-the auld days” and a person who was "rotten" (syphilitic) put inside it, to get "the tribble drawn oot." Told of "the wicked laird of B." A horse is also said to have been used.

Dog. On the advice of a "tinkler wife," a litter of black puppies was killed, split up, and applied warm to a septic wound on the arm. (Auchterderran.)

Donkey. Children are passed under the belly of a donkey to cure whooping-cough. Riding on a donkey is supposed to be a prophylactic measure.

Eel-skin is used as an application in sprains. It is often kept for years and lent out by the owner as required. It is kept carefully rolled up when not in use.

Hare. A hare-skin is worn on the chest for asthma. The left fore-foot of a hare is carried in the pocket as a cure for rheumatism.

Horse. The membranes of a foal at birth ("foal-sheet") are kept, dried, and used as a substitute for gutta-percha tissue in dressing wounds. The advice of the rider on a white or piebald horse is good for whooping-cough.

Limpet shells are used as a protective covering for "chackit " (cracked) nipples

Man. Saliva is rubbed on infants' noses to cure colds. "Fasting spittle" is used for warts and for sore eyes. Woman's milk is also used for the latter purpose. The smell of sweat is held to cure cramp : the fingers are drawn through between the toes to contract the smell. Urine is used as an application for "rose" (erysipelas). Rubbing a birthmark with the dead hand of a blood-relation will remove it.

Mouse. The "bree" in which a mouse has been boiled is used as a cure for bed-wetting in children. Or the mouse may be roasted, after cutting off its head, and then powdered down and given as a powder, both for bed-wetting and for whooping-cough.

Pediculi capitio are supposed to be "a sign of life" i.e. they only appear on the head of a healthy child. By a curious piece of confused reasoning I have known them to be deliberately placed on the head of a weakly child with the idea that the invalid would thereby gain strength.

Pig. A piece of ham-fat tied round the neck is good for a cold, bronchitis, or sore throat. "Swine's seam" (pig-fat) is an universal application for rubbing to soften inflamed glands ; to rub the glands of the throat "up" when they are "down" (i.e. when the tonsils are enlarged and easily felt externally) ; for sprains ; for rheumatism, lumbago, sciatica, etc. Pig's blood is a cure for warts. When the pig's throat is cut, the warty hand is applied to the gush of blood. Pig's gall is a cure for chilblains.

Skate. "Skate-bree" (the liquor in which skate has been boiled) is held to be an aphrodisiac. "Awa' an' sup skate-bree!" said tauntingly to a childless woman.

Slugs. The oil of white slugs is used as a cure for consumption. They are placed in a jelly-bag with salt, and the oil dripping out is collected. The oil of black slugs is used as an external application for rheumatism. The slugs are "masked" in a teapot with hot water and salt.

Spider. "Moose-wabs" (spiders' webs) are used to check bleeding, and are used as pills for asthma.

2. Vegetable Cures.

Infusions of nettles and broom-tops for "water" (dropsy).

Infusions of dandelion-root for "sick stomach."

"Tormentil-root " is used for diarrhoea.

Yarrow, horehound, and coltsfoot for coughs and colds. An infusion of ivy-leaves is used as an eye-lotion. Ivy-leaves are sewn together to form a cap to put on a child's head for eczema. Kail-blade (cabbage-leaf) is used for the same purpose. Ivy leaves are applied to corns.

Marigold leaves are applied to corns.

" Apple-ringie" (southernwood) and marsh-mallow poultices are used as soothing applications in pain, in "beelins" (suppurative conditions).

" Sleek" (long, thin, hairy seaweed) is used as a poultice in sprains, rheumatism, etc. (Buckhaven).

A "spearmint" poultice is used as a galactagogue.

Potato, carrot, and turnip poultices are often used.

Poultices of chopped leeks, of chewed tobacco-leaf, and of soap and sugar, are common for whitlows.

A potato carried in the pocket is good for rheumatism.

Freshly gathered nettles are used for switching rheumatic joints.

3. Mineral Cures.

Sulphur. Sulphur is a cure for cramp. A piece of sulphur under the pillow would protect all the occupants of the bed. It is sometimes worn in the "oxter " (armpit), and sometimes sewn in the garter, when it is called a "sulphur-band."

Flowers of sulphur are dusted into the stockings for rheumatism, or rubbed into blue flannel and applied for lumbago.

Sulphur and cream of tartar is taken as a "spring drink."

DEATH AND BURIAL.

If a corpse keeps soft and does not stiffen, there will be another death in the family within a year.

If two deaths occur in the place, a third will follow. This is a very common belief. The brother of a man who was seriously ill accompanied me to the door on one occasion and said, "I've sma' hopes o' him mysel', doctor; there's been twa deaths in the parish this week, and we're waitin' the third." The patient nevertheless recovered.

The clock is stopped at death ; the mirrors are covered, sometimes also the face of the clock; and a white cloth is pinned up over the lower half of the window (Auchterderran)

Cats are not permitted in a room where there is a dead body, owing to the belief that if a cat jumped over the corpse, anyone who saw the cat afterwards would become blind (Auchterderran).

A saucer with salt is sometimes placed on the chest of the corpse (this is not a general custom). Pennies are laid on the eyelids to keep them shut, and the falling of the jaw is prevented by propping up with a Bible.

The presence of the minister at the "chestin' " (coffining) is still quite common in Fife. This is the outcome of Acts of Parliament in 1694 and 1705, which enjoined the presence of an elder or deacon to see that the corpse was clothed, in the former case in linen, in the latter in woollen garments. See H. Grey Graham, Social Life in Scotland in the 18th Century, and ante, page 166.

PROVERBS.

A cauld hand and a warm heart.A' his Christianity is in the back-side o' his breeks (said contemptuously of one whose professions do not match with his mode of life)

A hoose-de'il and a causey-saint.

An ill shearer never gets a gude heuk.

As the soo fills, the draff sours.

A scabbit heid's aye in the way.

Auld age disna come its lane (i.e. other troubles come with it).

A woman's wark's never dune, and she's naethin' to show for't.

Betwixt the twa, as Davie danced.

"Ca'in' awa', Canny an' pawkie,

Wi' your ee on your wark an' your pooch fu' o' baccy." (An adage on the best way to work. Auchterderran.)

Daylicht has mony een.

Dinna hae the sau (salve) waitin' on the sair (i.e. do not anticipate trouble).

They're queer folk no' to be Falkland folk. (Possibly referring back to the days when foreigners were common at the palace.)

Falkland manners.

Fife.

He's Fifish.

He's a foreigner frae Fife.

He's a Fifer an' worth the watchin'.

It taks a lang spune to sup wi' a Fifer.

He's got the Fife complaint—big feet and sair een. (An "incomer's " saying regarding the Fifer, and naturally resented by him.)

He's got a gude haud o' Fife (of a man with big feet).

As fly as the Fife kye, an' they can knit stockins wi' their horns.Why the Fife kye hinna got horns ; they lost them listenin' at the Londoners' (Lothian people's) doors. (They were so astonished at the Lothian dialect that they rubbed off their horns in listening to it. N.B. —The Fifers have an old dislike for the Loudoners.)

Fools and bairns shouldna see half-dune wark.

Freens (= relations) gree best separate.

Go to Freuchie and fry mice ! (i.e. get away with you !).

He's as fleshly as he's godly (said of anyone laying claim to piety).

He has a gude neck (i.e. plenty of impudence. " Sic a neck as ye ha'e! ").

He pits his meat in a gude skin (said of a healthy child with a good appetite).

He's speirin' the road to Cupar an' kens it

He's speirin' the road to Kinghorn and kens't to Pettycur (i.e. some distance farther on).

He's ta'en a walk roond the cunnin' stane.

I'd soom the dub for't first (i.e. I would sooner cross the sea than do it).

It's lang or the De'il dee at the dyke-side.

It taks a' kinds to mak' a warl'.

Just the auld hech-howe (i.e. the old routine).

Marry the wind an' it'll fa'.

Maun-dae (must do, i.e. necessity) is aye maisterfu'.

Seein's believin', but findin' (feeling) 's the naked truth.

Sing afore breakfast, greet afore nicht.

Sodger clad but major-minded (i.e. poor but proud).

Spit in your e'e and choke ye.

That's a fau't that's aye mendin' (i.e. youth)

That beats cock-fechtin'.

The De'il's aye gude to his ain.

The nearer the kirk, the faurer frae grace.

They're no gude that beasts an' bairns disna like.

Twa flittin's (removals) is as bad as a fire.

When ye get auld ye get nirled.

[Whaur are ye gaun ?] " I'm gaun to Auchtertool to flit a soo." (Auchterderran. Said to impertinent enquirers. Auchtertool is a village in the neighbourhood about which there is a saying, and a song, "There's naught but starvation in auld Auchtertool.")

Ye canna be nice (particular) and needfu' baith.

Ye dinna ken ye're livin' yet (said to a young girl making a moan over any pain or suffering).

Ye'll be a man afore your mither (jocose encouragement to little boys).

Ye maun just hing as ye grow. (It is often said of neglected children, "they just get leave to hing as they grow. ")

Your e'e's bigger than your belly (said to a greedy child).

SCHOOLBOY SAYINGS.

"I'm no' sae green as I'm cabbage-looking."

"I'll spit in your e'e an' choke ye !"

"Spit owre that! " Said with hand extended ; challenge to fight.

"Coordie, Coordie, Custard ! " To a coward.

" Clypie, Clypie, Clashpans ! " To a tell-tale.

A boy going to school in a kilt would be greeted with :

" Kilty, kilty cauld doup, Never had a warm doup ! "

A child unduly proud of any article of dress would be humbled by the other children chanting :

"A farden watch, a bawbee chain, I wish my granny saw ye ! "

Any one wearing a new suit of clothes is given a severe nip by his comrades. This is called " the tailor's nip.”

WEATHER LORE.

Crows flying about confusedly, rising and falling in the air, means windy weather to follow.

"A near hand bruch (halo round the moon) is a far awa’ storm : a far awa bruch is a near hand storm."

"There's somethin' to come oot yet," said when cold weather persists continuously, or " There's somethin' ahint a' this."

"It's blawin' through snaw." Said of a cold wind.

"It's waitin' for mair," said of a persistent wreath of snow on a hill-top or hill-side.

A duck looking at the sky is said to be "lookin' for thunder."

"Rainin' auld wives," "Rainin’ cats and auld wives," and "Rainin' auld wives and pipe stapples (pipe-stems) " are all said of a heavy wind and rain storm (i.e. the kind of weather witches would be abroad in).

"When mist comes frae the sea

Gude weather it's to be,

When mist comes frae the hill,

Gude weather it's to spill."

"Mist on the hills, weather spills,

Mist on the howes, weather grows."

(Of the/position of clouds in the sky.)

"North and South,

The sign o' a drouth ;

East and Wast,

The sign o' a blast."

"Clear in the South droons the plooman."

"It's cauld ahint the sun " (i.e. warm when the sun is out, but cold when it sets).

"If the oak afore the ash,

Then we're gaun to hae a splash ;

If the ash afore the oak,

Then we're gaun to hae a soak."

"Rain in May maks the hay,

Rain in June maks it broon,

Rain in July maks it lie."

FISHERMEN'S FREITS. (Folk-Lore, vol. xv. p. 95.

My principal informant on this part of the subject, with whom I have gone over Miss Cameron's paper on "Highland Fisher Folk and their Superstitions " (Folk-Lore, xiv. 300-306) in detail, is an intelligent elderly man who has alternately worked in the pit and the boat for over thirty years. His acquaintance with the subject is thus pretty thorough, and many of the customs and beliefs have been impressed on him through his being "checkit " for breaches of them. I found that the great majority of " freits" mentioned by Miss Cameron are still common to "the Kingdom." Some small additions and differences I will mention here.

"Buying wind," if it ever existed in Fife to the same extent as in the Highlands, has now degenerated into cultivating the good-will of certain old men by presents of drinks of whisky. The skipper of the boat "stands his hand " (i.e. stands treat) freely to those worthies before sailing. " Of course it's a' a heap o' blethers," said my informant, " but a’ the same I've kent us get some extra gude shots when the richt folk was mindit."

If one of the crew while at sea carelessly throws off his oilskins so that they lie inside out, an immediate rush is made to turn the exposed side in again. Should this not be done it is apt to induce dirty weather.

At sea it is unlucky ... to mention minister, salmon, hare, rabbit, rat, pig, and porpoise. It is also extremely unlucky to mention the names of certain old women, and some clumsy round-about nomenclature results, such as "Her that lives up the stair opposite the pump," etc.

But on the Fifeshire coast the pig is par excellence the unlucky being. "Soo's tail to ye!" is the common taunt of the (non-fishing) small boy on the pier to the outgoing fisher in his boat. (Compare the mocking "Soo's tail to Geordie!" of the Jacobite political song.) At the present day a pig's tail actually flung into the boat rouses the occupant to genuine wrath. One informant told me that some years ago he flung a pig's tail aboard a boat passing outwards at Buckhaven, and that the crew turned and came back. Another stated that he and some other boys united to cry out in chorus, "There's a soo in the bow o' your boat !" to a man who was hand-line fishing some distance from shore. On hearing the repeated cry he hauled up anchor and came into harbour. There is also a Fife belief (although it is chiefly spoken of now in a jesting manner) that after killing a certain number of pigs (some put the number at ten) a man runs the risk of seeing the devil. The hole in the pig's feet is shown through which the devils entered the Gadarene swine. In the popular mind there is always a certain uncanniness about swine, which is emphasised by the belief that a pig sees the wind. It is further said that a pig cannot swim without cutting his throat, and so must inevitably die in the attempt to escape drowning.

It is strange that although it is unlucky to mention the word hare while afloat, the leg of a hare should sometimes ... be carried in a boat for luck. The fisherwomen of the Forfarshire village of Auchmithie (the " Mussel Crag " of Scott's Antiquary) used to be irritated by school children shouting out, "Hare's fit in your creel"; also by counting them with extended forefinger and repeating the verse

Ane ! Twa ! Three !

I do see ! "

The unluckiness of counting extends to counting the fish caught or the number of the fleet.

While at the herring-fishing each of the crew is allowed in turn the honour of throwing the first bladder overboard when the nets are cast at night. Before doing this he must twirl the bladder thrice round his head and say how many "crans" the night's fishing will produce. Should the catch fall below his estimate, he is not again allowed, on that trip, to throw the first bladder ; but if successful he throws again the next night.

The Fifeshire fisher does not scruple to eat mackerel, but states that the Highlandman will not do this, owing to his belief that the fish turns into "mauchs " (maggots) in the alimentary canal. . . .

The body of a drowned man is supposed to lie at the bottom for six weeks until the gall-bladder bursts. It then comes to the surface. A man's body floats face downwards : a woman's, face upwards.

In the coast towns and villages of Fife a curious custom prevails with regard to the treatment of any carcase, say of a clog, cat, or sheep, that may be cast up on the beach. School children coming across anything of the kind make a point of spitting on it and saying, "That's no my granny," or "That's no freend (i.e. relation) of mine." Others simply spit on the carcase, giving as a reason that it is done to prevent it "smitting " (i.e. infecting) them. Almost everyone on perceiving a bad smell, spits.