The Health Conditions Of Coal Mining

By James Barrowman, Mining Engineer

Presented at the General Meeting of The Mining Institute of Scotland, 13 June 1896

A few years ago a candidate for parliamentary honours in addressing an audience of colliers in Hamilton, exclaimed in a fine frenzy that he saw death stamped on their faces. The statement was not received with that enthusiasm which the speaker no doubt expected, probably because it lacked the flavour of flattery, so agreeable to every one, and was not self-evident enough to be accepted by the audience as true. Who can tell what influence these few words had in placing him at the bottom of the poll ?

That exclamation illustrates a very widespread belief, which frequently finds utterance at miners' meetings and in speeches delivered in the miners' interests, namely, that the coal-mining industry is particularly unhealthy. If it be so, it is well that the fact should be firmly established and widely known; if it be not so, the true state of the matter should be published no less widely.

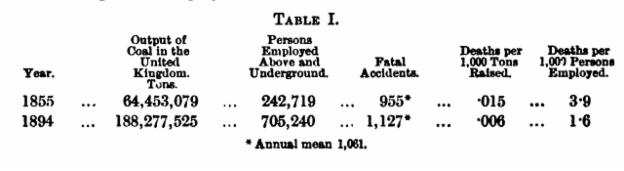

It cannot be denied that coal mining is a dangerous occupation. With, perhaps, the exception of the railway industry, it is more prolific in accidents, fatal and otherwise, than any other occupation in this country. The annual reports of the inspectors of mines serve not only to keep this fact always before us, but they preserve a correct record of the nature and number of mining accidents. They also show, however, the progressive improvement that has taken place as regards safety in the occupation of the collier, and this has some bearing on the figures relating to health, referred to later on. Comparing the figures for 1855 with those for 1894, for example, as shown in Table I., it will be seen that while the number of fatal accidents has fluctuated little, maintaining an average rate over the past forty years of 1,061 per annum, the output and the number of persons employed have increased almost threefold.

There is no doubt that the health conditions of coal-mining have also greatly improved within the same period. This can, of course, be said of all occupations, and of the people as a whole; but apart from this general improvement, we want to know if there are diseases peculiar to coal-mining which have the effect of shortening the life of the miner, or, if those diseases which are common to all, are aggravated by mining conditions to such an extent as to justify the statement that the coal-miner is a short-lived man. When we consider that about one-fifth of the whole male population of the United Kingdom, between the ages of 25 and 65, are miners, it will be recognised that the question is one of some consequence.

It is matter for surprise that this subject has received little attention in this country. As regards Scotland, there are no statistics published from which a comparison can be made of the health conditions of persons engaged in different occupations. Mortality tables for England and Wales have been published; but there are no statistics made up for the country as a whole, and those which are available are fifteen years old. It may, however, be safely assumed that if the conclusions arrived at after examination of the particulars collected fifteen years ago are well founded, the results would be more favourable if later statistics were available, seeing that there has been an obvious advance towards a better state of things. Apart from the statistics referred to, there are probably valuable particulars, which have been collected by individual observers in isolated districts, but these appear to be few.

As to whether there are any diseases peculiar to the miner's calling, there is evidence that, with one, or perhaps two, exceptions, there are none such. These exceptions are an affection of the eyes, termed "nystagmus;" and, in a lesser degree, that disease of the respiratory organs which usually goes by the name of "miners' asthma."

Nystagmus, although not a prevalent affection, is one with well-marked symptoms, directly traceable to the posture of the collier while at work. The symptoms are oscillation, with more or less of a rolling motion of the eyeballs; giddiness, with headache, and the appearance of objects moving in a circle, or lights dancing before the eyes. In severe cases the person affected may stumble and be so much inconvenienced as to be obliged to stop work. Dr. Simeon Snell, of Sheffield, has given this disease special attention for about twenty years, and has published the results of his investigations [Miners' Nystagmus. By Simeon Snell, 1892.], which show beyond all reasonable doubt that nystagmus is confined almost entirely to those underground workmen who are engaged in holing or under-cutting the coal, and is due to the miner's habit of looking upwards, above the horizontal line of vision, and more or less obliquely while at work lying on his side. It has been observed also in firemen and others who have occasion frequently to examine the roof, turning the eyes obliquely while doing so. Any other occupation in which the person may habitually turn the eyes upwards and sideways will induce nystagmus ; but such cases are so rare that this trouble may be regarded as one peculiar to mining. Turning the eyes downwards yields temporary relief; but there seems to be no permanent cure for it except abandonment of the kind of work that gave rise to it.

It has been alleged that the use of safety-lamps in the mines, giving less light than the open candle or lamp, has aggravated this disease; but the careful and long continued observations of Dr. Snell, and of Mr. A. H. Stokes, [Reports of H. M. Inspector of Mines for the Midland District, 1890, 1891.] prove that there is no connexion between the use of safety-lamps and the alleged increase of nystagmus. The number of miners is on the increase, and greater attention has been given of late to this affection than formerly, which circumstances sufficiently account for the supposed relative increase in the number of cases. Other specialists in this country and on the Continent confirm the conclusions of Dr. Snell.[Dr. Tatham Thomson, Lancet, 1891, vol. i, page 311 ; Mr. Jeaffreson, British Medical Journal, 1887, vol. ii., page 109 ; and Dr. Dransart, Journal d'Oculistique du Nord de la France, August, 1891.]

The disease, called miners' asthma, with which a characteristic black spit is associated, cannot be said to be special to mining in the same sense as nystagmus is, as there are other occupations in which a similar disease is prevalent, such as those of quarriers, masons, and pottery makers; still the conditions of underground occupation appear to be conducive to the extension of this and related diseases of the respiratory organs. It is clear to an ordinary observer, that, within the last quarter of a century there has been a great improvement in coal-miners in this respect, and that those who suffer from diseases of the respiratory organs are relatively fewer now than they were twenty-five years ago. We do not require the evidence of vital statistics to convince us of this, and we can have no difficulty in attributing this better state of things to the great improvement in ventilation effected within the time mentioned.

But it is from a comparison with the workmen in other occupations that the most definite results as to the health conditions of mining are to be got. The information available for the purpose is contained in a series of tables prepared by Dr. Ogle, the superintendent of statistics in the general register office, from particulars collected at the census of 1881, and from similar figures collected by his predecessor, Dr. Farr, at earlier dates. In Dr. Ogle's tables, six coal-mining districts in England and Wales are selected, namely, (1) Durham and Northumberland, (2) Lancashire ; (3) the West Riding of Yorkshire ; (4) Derby and Nottinghamshire ; (5) Staffordshire; and (6) South Wales and Monmouthshire. It is to be regretted that there are no published statistics for Scotland.

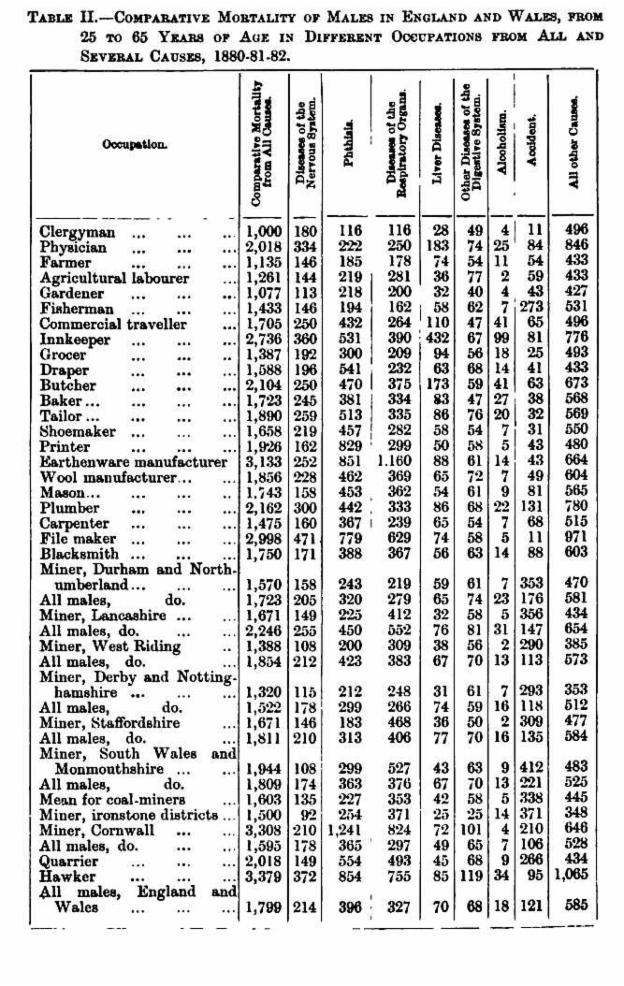

Dr. Ogle gave evidence, in 1892, before the Royal Commission on Labour, and then submitted a series of tables, an abstract of one of which appears on the following page (Table II.). Table II. shows the number of deaths that took place annually in the years 1880, 1881, and 1882, in 116,261 males of each occupation stated, of whom 75,396 were between 25 and 45, and 40,865 between 45 and 65 years of age. This population was selected as being that in which 1,000 deaths of clergymen occurred annually, being the lowest death-rate of all. Those described as coal-miners include aboveground as well as underground workers in connexion with collieries. The results shown by Table II. are very different from what popular belief would have led us to expect.

Comparing the deaths of coal-miners in the six districts referred to under the several headings in Table II. with the deaths of all males of a corresponding age in England and Wales, we find that, with only two exceptions, the death-rate of coal-miners is the lower. These exceptions are accidents and diseases of the respiratory organs. We should expect these two causes of death to rank high with miners; but the comparison in the case of the other causes of death is so favourable for miners, that, on combining the figures for all causes of death, including accidents and diseases of the respiratory system, the death-rate of the coal-miner still stands lower than the average of the country. It is noticeable also, that if the coal-mining districts be taken separately, the deaths of miners in each, with the one exception of South Wales, are less than the deaths of all males in the same district.

In case it may be thought that comparison with all males is not a fair one, let some of the occupations be selected to which dust or high temperature, or both, are incident, and still the comparison is in favour of the coal-miner. The baker, the blacksmith, the mason, the wool-manufacturer, the quarrier, the file-maker, and, notably, the earthenware manufacturer, have all a much higher death-rate; indeed, we have to go to the occupations which are recognized as the most healthy to get a close agreement with the coal-miner.

In drawing attention to the high death-rate in miners from diseases of the respiratory system as compared with that from phthisis, Dr. Ogle refers to the somewhat loose way of certifying death, and expresses the opinion that many deaths registered under the name "miner's phthisis " should really be under one or other of the diseases of the respiratory organs, and that there should be an addition to the number of deaths from the latter and a corresponding reduction in the number of deaths from phthisis. What this addition should be it is impossible to say; but although it were considerable, there are still, as shown in Table II., a number of occupations having a higher death-rate from diseases of the respiratory organs. If, as suggested by Dr. Ogle, an addition should be made to the figures in the column under diseases of the respiratory organs, and a corresponding deduction from those under phthisis, then the latter will occupy a surprisingly low place relative to deaths from that cause in other occupations. As it stands in Table II. there are few occupations with greater immunity from phthisis than coal-mining, and if the figures be reduced we must turn to the very healthiest occupations, such as that of the fisherman, the farmer, and the gardener for an equal comparison.

The comparative immunity of coal-miners from phthisis has been the subject of observation by medical men, both in this country and on the Continent. Dr. Nasmyth [Trans. Min. Inst. Scot., vol. x., page 161.] found that in the parish of Beath in Fifeshire, for the twelve years from 1876 to 1887, the death-rate from phthisis was 1.01 per 1,000 for miners, as compared with 1.72 for females and 1.33 for both sexes. The opinion has been firmly expressed by at least one Continental writer [Arbeiter-Schutz, by Dr. Hirt, 1879, page 19.] that the coal-dust inhaled into the lungs by the coal-miner has a preservative influence, and to some extent prevents consumption. An examination of coal-dust under the microscope shows that the particles are rounded, and on that account much less likely to irritate the lungs than the heavier and more angular dust made by the mason and the quarrier.

The death-rate of coal-miners from alcoholism is particularly low, which goes to show that the occasional drinking to excess indulged in by many of them is less deleterious in its effects than the more frequent tippling of men in some other occupations.

In comparing the figures for the six several coal-mining districts, one is met with differences the cause of which is not apparent. South Wales and Monmouthshire have a much higher death-rate than any of the others, and this suggests the enquiry, what relation will Scotland bear to these districts? The workings of the collieries in Scotland being in general not so extensive nor so deep as those in England and Wales, it is probable that, on the whole, the underground air is purer, and the extremes of temperature not so wide in Scotland as in England and Wales; and it may be safe to assume that the average figures of the six coal-mining districts already referred to will form a fair basis for the mines of Scotland.

Because of the very favourable aspect in which the figures on Dr. Ogle's table place the coal-miner as compared with men in most other occupations, we are disposed to criticize his table with the view of finding out whether the method of compilation is sound. A few objections may be mentioned, some of which Dr. Ogle has anticipated and answered.

It is obvious that, to a certain extent, coal-miners are picked men. Those who are lame, blind, and otherwise infirm, will not choose this occupation; and those who by accident are disabled for active exertion must leave it. For these reasons the figures in the table will tell too favourably for the coal-miner, seeing that the population, as a whole, includes all infirm persons. But the same may be said of several of the occupations named on the table, such as quarriers and blacksmiths, and yet these have a higher death-rate than the miner.

The death-rate from accident being so high in the coal-mining occupation, there must be a corresponding decrease in the number of deaths from natural causes. To this extent the table shows too favourably for the miner from a health point of view; but, as has already been noticed, the deaths from all causes, including accident, are in the case of coal- miners less than those of most other occupations enumerated in the table. Moreover, we have seen that the deaths from accident have been proportionally much reduced during the last forty years. The small error due to this cause must, therefore, be of less account in each succeeding census.

Another point that suggests criticism is, regarding the period of life embraced in the table. A coal-miner has ten years of his working life past at the age of twenty-five, and many leave pit-work before the age of sixty-five. It may be answered, however, that whilst that is so, the same may be said of other workers mentioned in the table; and that on the whole, especially with those industries with which one would most readily form a comparison - that is, labouring occupations and trades, - they are substantially on an equal footing.

It has to be borne in mind that no mortality-table can present the facts with absolute accuracy. At the same time there seems no good reason to doubt the general reliability of the table as a statement of relative health conditions.

On the whole, therefore, we have good grounds for regarding the occupation of the coal-miner as one of the healthiest; and even after including deaths from accident we see that the mortality among coal- miners is less than that of most manual occupations. In the Report of the Royal Commission on Labour, 1892, the opinion of the committee on this subject is stated as follows:-

The weight of evidence seems to be against the idea that coal-mining is an unhealthy occupation, even when allowance is made for the probability that weakly men either avoid or soon abandon it.

There are several circumstances which may be regarded as contributing to the evidence that the health conditions of the coal-miner are favourable.

In the first place, the underground temperature is equable, and on the whole, not uncomfortably high. That these are favourable conditions receives some corroboration from the fact that pit ponies, although confined underground for years, thrive and keep up in flesh and appearance even better than when worked on the surface. The regular temperature of the air seems to more than make up for the want of daylight. No doubt an excessively high temperature, especially if accompanied by a moist state of the air, is bad, but the former is confined to the very deep mines, and a conjunction of the two is not common. The sudden change from one extreme of temperature to another, when the miner comes out of the pit on a winter's day, is what most readily leads to diseases of the respiratory organs, and should be provided against more effectually than is the custom.

In the second place, the bulk of the coal-miners live in rural communities, and have the benefit of fresh air.

Thirdly, the coal-miner's working day is a comparatively short one, and he seldom works every day in the week. The Scottish collier has always had a hankering after a weekly holiday. As far back as the year 1641 an Act of the Scottish Parliament was passed ordaining colliers and other colliery workmen to work all the six days of the week, the reason given being that they had been in the habit of taking frequent holidays, which they spent in "drinking and debauchery, to the great offence of God and prejudice of their masters." Like many other of the early Acts this one was pretty much ignored; at any rate we find that towards the end of the next century five days was the ordinary week's work in the collieries.

Good as things are, we hope to see them better. We cannot entirely do away with all the causes of death and disease, but strenuous efforts are being made to lessen their effects. The composition of the gases met with in mines, and their effect on the human system, are receiving most careful attention from Dr. Haldane, Dr. Clowes, and others. Ventilation has been brought to a high state of efficiency; the resources of science are taxed to provide an explosive that can be used without the risk of igniting fire-damp, as the labours of the Flameless Explosives Committee show. Better dwellings and improved sanitary arrangements are now the rule. All these are tending towards the bettering of the health conditions of coal-mining.

______________

Mr. Malcolm (Arniston) mentioned that he had taken a census of the miners in a working where 40 miners were employed, and he found 11 of them whose average age was 74 years.

The President said that he found in connexion with colliery friendly societies that underground workers drew less money than those engaged on the surface.

The discussion was adjourned.