Miscellaneous

Dalbeath Colliery To Close - Much dismay has been occasioned by the announcement of the closing down of No 2 Pit Dalbeath Colliery as from the 23rd of this month. On inquiry it was learned that this will affect 100 men, very few of whom will be put up at other pits. Nearly all of the men reside in Hill of Beath, which will increase the depression already existing in that village. [Dunfermline Journal 20 October 1928]

From Dunfermline To Lassodie

A stranger desirous of seeing the mineral fields of the West of Fife can spend a day very profitably in visiting the collieries that lie between Dunfermline and Lassodie. The access to Lassodie is very difficult, and the traveller, with three available routes before him, can have but one choice, and that is to take the road by Kingseat Hill, and thence through the village of Kingseat itself. All the way the road is one long "hill of difficulty," but the pedestrian will find it interesting in many ways. Leaving at the cross roads at Towngreen Old Toll-house we proceed direct north through Gardener’s Land, at the top of which we get a splendid view of "the Auld Grey Toon" and its immediate surroundings. On reaching the summit of Kingseat Hills a still more enchanting view is obtained of various reaches of the river Forth and the three Lothians. Two cottar houses are built on the hill, and looking east we see in the distance the thriving village of Townhill.

Since the Townhill Coal Company settled down in the village some sixteen years ago the place has rapidly increased, and is improved in many ways. Year by year the tenants of the colliery have increased the area of their field, giving to the burgh a large and annually increasing revenue. At the entrance of the village there is the brickwork of Mr Richard Strut, who has been four years located in the village. Nearly six years ago Mr Muirhead, a cattle salesman and experienced farmer, and who had had a thriving spirit and grocery store at Quarter, near Hamilton, came and settled down in Townhill, and the change over the extensive property he owns, and the remarkable progress of the village in these years is unparalleled in the history of the West of Fife. For over sixteen years the village had been without a public-house, and singular to say in one year such a house was opened by Mr Muirhead, and in three months afterwards a new church was opened, with the Rev. Jacob Primmer as its first minister. Since then the church has got a bell and a public clock, and gas and water have been introduced into the village. North from the village stands Lilliehill Brickwork, which employs over 60 men and boys. Near the village also are the four farms belonging the burgh. viz., Lilliehill, Cairncubie, Muircockhall, and Highholm, the total acreage being about 600 acres. To the east there is the new colliery of Muircockhall, which was let on lease to the West of Fife Coal Company in 1868. This thriving Company have since entering on their lease built several fine rows of houses, the most of which are in Townhill village, and lie straight west from Mr Muirhead`s properties, and stretch away down to the shores of the Loch, which is famed for the quantity of trout it contains, and as being the spot where skaters most do congregate when the ice is in its strength.

Returning to Kingseat Hill we go straight east, away by Muircockhall Colliery, and going right behind the Hill of Beath we come to the rising village of Kingseat. At the north-west side of the Hill of Beath a large school has been erected, which accommodates the children residing in Halbeath and Kingseat. Before entering Kingseat we get a glimpse from the south of the Halbeath Colliery, many of the pits of which are now well nigh wrought out. There is nothing remarkable about Kingseat, which is wholly tenanted by miners. It has one public-house and a licensed grocer`s premises, a small hall, but no public buildings. Leaving the village we cross the hill, and in the valley below we see Hensneb Colliery, and going east come to Hamilton’s store. Here we come to two cross roads. The one leading due east leads to Kinross and the Great North Road, and the one direct north takes the traveller right into Lassodie Colliery village.

The first house we come to is the palatial residence of Mr Brownlee, under whose care and by whose able management the village has thriven and attained its present size and prosperity. North from this we come to the school and schoolhouse. The present teacher is Mr David Ayton, who for over five years was head-master in the Commercial School, Dunfermline. The teacher’s house is a commodious building of two storeys, and having behind it a large garden. The school is really a splendid building, and was erected a few years ago from plans prepared by Mr Andrew Scobie, architect, Dunfermline. The school at present is attended by 240 children. The main room and classrooms of the school are lofty and airy and the apparatus excellent. The present staff of teachers consists of one headmaster, one female teacher, and three pupil teachers. The playground is spacious, and the whole buildings a credit to the Beath School Board. The village is like most colliery villages - the houses being most or generally all constructed of brick - but in accommodation and for finish and general comfort the miners’ houses at Fairfield, Lassodie, excel those of any colliery in Fife or Clackmannan. There is a prosperous co-operative store in the village. At the east end a church has been erected, which is in connection with the Free Church, and attached to the Presbytery of Kinross. The Rev. Mr Clark is the present minister of the church, and the membership is very strong. Near the church a fine manse has lately been built, and a bazaar to assist in defraying the cost of its erection will be held in Dunfermline this spring, when, doubtless, all denominations in Dunfermline and the West of Fife will give what aid they can to raise sufficient money for this not unworthy object. Altogether, one cannot but be pleased with a visit to Lassodie, and that the village is there, with all its institutions and its rapid rise and progress, a testimony of the perseverance and the genius of one single man Mr John Brownlee.

Going down the West of Fife Mineral Railway, we leave Lassodie, and quitting the line, walk up the Valley of Balmule. Here it was that for several years a remarkable family was located. We refer to the Hutchisons of the Valley. In early years the three brothers - William, John, and James - lived, and the work of their hands is to be seen at every farm steading, and in almost every mansion near Dunfermline. Quitting the quietude of the Valley, the brothers settled down in Dunfermline, and their industry is seen to advantage in the Victoria Works at Grantsbank, and in their last and greatest work, the erection of the Corporation Buildings, Dunfermline. At the entrance to the Valley of Balmule we reach Lochend, on the Crieff Road. Going straight south, we reach Wellwood village and colliery. At the north end of the village we find a grand school and schoolhouse, with a large playground. The present teacher is Mr Alex. Dawson, assisted by Miss Jessie Carson. The school buildings are replete, and for general efficiency cannot be matched in Fife. The rows of miners’ houses are neat and comfortable. In this village and in Milesmark reside a number of widows and aged men, for whom Mr Spowart of Broomhead makes generous provision. South from Wellwood is the estate of Broomhead, which is the summer residence of Thomas Spowart, Esq. Broomhead House is a large modern building surrounded by spacious policy grounds, and having a fine carriage drive, with entrance from Castleblair, and also from the Crieff Road. In front of the mansion house is a fine bowling green and a spacious lawn, and near it a summer house, vinery, &c. To the east of Broomhead are the lands of Venturefair, also the property of Mr Spowart, and a mile south the estate of Woodmill, which passed into Mr Spowart’s possession a few years ago. From Broomhead we come to Grantsbank, at the southern portion of which are the Victoria Works owned by Messrs Inglis & Co., and opposite the Dunfermline Foundry, where nearly 100 hands are employed, and where dozens of powerlooms are made weekly. The above is a brief sketch of our journey to and from Lassodie, and we trust it will interest our numerous renders. [The Dundee Courier & Argus and Northern Warder 13 January 1880]

The Past, Present & Future Of Donibristle Colliery

The Pits Of Olden Time And The Pits Of Today

How The Old Pits Were Drained Of Water

Aberdour As A Coal-Shipping Port

It is impossible to say when coal was first worked at Donibristle, but in the ecclesiastical and other records one stumbles now and again upon entries which give rise to the idea that the coalfields of the parish of Aberdour were stopped at the crop in the ancient days when work was proceeding on the adjoining parish of Dalgety.

In The Ancient Days

For instance, on March 11, 1697, we have the Kirk Session enacting: "That no seaman, master or servant in this parish presume to cross the water to Leith, as hath been custom upon the Lord's Day, with coals or any other goods on pains of being rebuked before the congregation and a penalty to the box of £1". The Rev. Alexander Scott was the minister for the parish in the beginning of the eighteenth century. He met with his Session for the last time on 22nd February, 1721, and then the Kirk box was opened. The astonishing sum of £674, 18s and seven bonds for big sums were found in the box for the poor of the parish. The prosperous conditions of things was attributed to the Coal Trade. Dr Ross, the historian of the parish says: "The coal trade at that time was giving full employment to a great many, and this not only at the north end of the parish where the pits were, but to those who were employed in carting the coals to the harbour, those who loaded the vessels there, and to the skippers and others who traded between the harbour and Leith. The shipping trade was evidently extensive". To this day there is a street in the village which takes the name of the "Coalwynd". The coalfield of the parish lies between the burn to the north of Monziehall Farm and the North British Railway which runs along the north edge of Moss Morran. The coal-workings of the olden time were continued to a point near Monziehall Farm, and were of the most primitive type. The coal was struck at the crop, and the seams followed by mines, the workings being kept free of water by levels carried in from the burn. Then it was found impossible to drain the lower section of the field by the levels running to the burn, the old people came further north where the coal gets thrown up by a dyke and carried in a water level from a clump of trees near Earl's Row to Moss Morran. This level drained the coals of the central section of the field, to a depth of eight fathoms. In summer, when there was little surface water, dooks were run in the coal seams for considerable distances below the level of the water courses. The water which collected at the lower depths was ladled from dam to dam, and in course of time this laborious system of drainage was superseded by wooden pumps.

Relics of the Olden Time

Relics of the old pumps, of the wooden ladles, and wooden picks, pointed with iron, have been found in recent years in the old workings. In the lower section of the coalfield near Monziehall Farm there is only covering for three coal seams - the Dunfermline Splint, the Five-Foot, and the Mynheer. A little to the north of the old-time workings, the Blaw lowan or Glassee seam takes on, and as we come further north, in Moss Morran, we have as many as five seams above the Glassee, including the Parrot, the Lochgelly Splint, and the Dudy Davie. Having only found three seams at Monziehall, the miners of the eighteenth century seemed to have thought that only three seams should be struck in other parts of the coalfield. In the stretches of coal that were struck in the southern slopes of Moss Morran, the Dunfermline Splint, the Five-Foot, and the Glassee was left untouched. In these modern times it is difficult to see how the omission was made, because the Mynheer is a hard, splinty coal, and is one of the finest household coals in the district, while the Glassee is only used for steam purposes. Although beaten in the old levels by the floods of water which came into the working from Moss Morran, the coal owners and miners of the bygone age of which we write, do not seem to have been prepared to abandon the workings. To the west of Earl's Row, in the meadow, a pit was sunk to a depth of several fathoms and a water wheel placed upon it at a considerable outlay. At several points the water was stored on Bucklyvie Farm in the hope of finding sufficient water power to drive the wheel. The pit was sunk to the Mynheer seam; but it is evident from the condition in which workings were found that the pump had fallen short of expectations, and the water wheel pit and the mining of coal at Donibristle Colliery were abandoned - the toilers finding employment at the neighbouring collieries, or returning to the lands on which the fathers of many of them had eked out an existence.

In the Year 1830

In the year 1830, Mr. George Grieve and Mr. Alexander Nasmyth, the father of Mr. James A. Nasmyth, the senior partner of the Donibristle Colliery of today, joined hands and took a lease of the coalfield of Donibristle from the Earl of Moray. There is a great difference between the colliery fittings of 1630 and 1901, but Messrs Grieve & Nasmyth tackled the field with such fittings as then could be procured. The first pit was sunk on the Monziehall Farm, the Dunfermline Splint or lower seam being struck at a depth of 20 fathoms in the Earl's Pit. A pretty good hold was taken of the Splint and the Five-Foot seams. A fortunate thing for the company was the fact that at a neighbouring colliery the working were on a lower level that the working of Donibristle, and the flood of water which had overwhelmed the mines of Donibristle in the olden time, and had ultimately led to abandonment, had vanished. The daily growth of water also found its way to the sea through the same channel. A second pit, the Ainslie, was soon sunk, and, considering the times, the output of the colliery became fairly large. Great enterprise was shown in the disposal of the coals. Only a small proportion of the output was disposed of locally, and there was no railway.

Shipping At Aberdour

The Company, following the example of the Day Mine miners, made Aberdour the point of connection with the outer world. A mile and a half of road was made from the colliery to the Aberdour Road, and an agreement was made for paying a portion of the upkeep of the highway between Aberdour Harbour and the Colliery Road. Along this road of three miles as much as from 120 to 125 tons a day were often carted and shipped at Aberdour. As many as 50 carts were often on the road, and from early morning until late in the evening the echo of the rattle of the Donibristle Colliery carts could be heard at the Goat and Whitehill plantations. In fact, in the busy shipping season - the summer months - when fleets of small sailing craft arrived from the Baltic and Dutch ports, carting was continued during the night from the colliery, and at the same time the stock of 250 tons, which had been built in the coal fauld at Aberdour in slack seasons, was drawn upon. Before the colliery was connected with the North British Railway, an output of from 30,000 to 40,000 tons a year was disposed of in the manner indicated. Compared with the colossal output of some collieries of modem times this looks small indeed; but when the means of conveyance and all the circumstances are kept in view, even the practical mind must be driven to the conclusion that nothing short of a conquest was achieved. The connection with the railway changed the whole aspect of things on the Aberdour Road, and at the old harbour of the ancient village. In the days of which we write, the harbour was crowded in the month of July with sailing vessels, and from morning until night there was a continual rattle of coal in the holds of the foreign craft. To-day there is not a vessel to be seen, and instead of the schooner and brig and the sloop weighing anchor we hear only the whistle of the Galloway streamers, the splash of the oars of a fleet of small pleasure boats, and the merry voices of the children of the visitors who have hied themselves to the Brighton of the North to seek for pleasure and health.

Changes of Modern Times

While the transformation has been made at the village of Aberdour, great changes have been experienced at the Donibristle Colliery. Mr George Grieve, Mr Alexander Nasmyth, the founders of the firm, have long since gone to their rest. The colliery is now one of the best appointed in the county of Fife, and instead of from 30,000 to 40,000 tons of an output annually, the output has been raised to from 120,000 to 130,000 tons. Here is a list of the pits which have been sunk between Monziehall and the railway since 1830:-

1. Earl's Pit - 20 fathoms to Dunfermline Splint

2. Ainslie Pit - 20 fathoms to Dunfermline Splint

3. Countess Pit- 30 fathoms to Dunfermline Splint

4. Meadow Pit- 10 fathoms to Dunfermline Splint

5. Dean Pit- 10 fathoms to Dunfermline Splint

6. Relief Pit - 25 fathoms to Mynheer

7. Catherine Pit - 30 fathoms to Mynheer

8. Isabella Pit - 60 fathoms to Dunfermline Splint

9. Moor Pit - 15 fathoms to Lochgelly Splint and Parrot

10. Adams Pit - Crop of Dunfermline Splint Coal.

11. Ashley Pit - 30 fathoms to Lochgelly Splint and Parrot

12. No. 12 Pit - 100 fathoms to Dunfermline Splint

13. Marion Pit - 100 fathoms to Dunfermline Splint

14. James Pit - 105 fathoms to Dunfermline Splint

15. No. 15 Pit - 105 fathoms to Dunfermline Splint

The Old Pits

To the older people of Donibristle and district the names of the old pits will recall many incidents on mining in the olden time. Women worked in the Earl's pit and other pits, and No. 11 Pit was called the Ashley because it was the first shaft sunk after Lord Ashley's Act of 1842 was passed, by which women, and children of tender years, were precluded from entering the mines.

The Countess Pit was sunk between the Earl's and the Ainslie, and with the Countess a new development in the history of Donibristle Colliery was witnessed. On the Earl's and the Ainslie the motive power of raising the coals to the surface was the horse gin. On the Countess Pit a steam winding engine was erected, and the seams being at a lower level than anything previously worked, a pumping engine had to be faced. The Dunfermline Splint was struck at a depth of 30 fathoms, and because of a fault which constituted a "slip down", the Mynheer was gotten at a much lower depth than it had previously been touched. We give a drawing of the fittings of the Countess Pit, taken from a sketch in 1838 by Mr Perry, artist. As already indicated the Countess Pit was considered a big mining venture in 1833, and it is interesting to contrast the fitting with the great pits of today. It will be noticed that there were no cages, and no guides in the shaft. The boxes were decked on to the rope and taken off and on to trams at the bottom and mouth of the shaft. In ascending and descending, men had to keep a watchful eye on the passing cage. The pithead frame was very high, and the pulleys small, the pumps were raised and lowered by a crab, and the pumping beam was of wood balanced, as will be seen from the sketch, with an old pump laden with cast-iron. The Meadow Pit struck the coal at a point near the crop, which accounts for its shallowness, and the same falls to be said of the Dean Pit. The first five pits were sunk to the south of the Kirkcaldy Road - the old school being the site of the Dean. With the Relief Pit, attention began to be devoted to the field to the north of the public highway. Pumping and winding engines of same pretensions were placed on the Catherine, which was sunk to the Mynheer seam; and, strange to say, the Dunfermline Splint was gotten at the same depth, having been thrown up by a dyke at a point in the field right opposite the Mynheer. In 18?? the company moved a little further north, and then tackled the greatest undertaking they had yet attempted - the Isabella or No. 8 Pit. It was here that the upper section of the coalfield of the Parish was really tapped, and the Lochgelly Splint and Parrot, the Blawlowan, the Mynheer, the Five-Foot, and the Dunfermline Splint were struck.

The Pits of Today

Operations are now suspended at the Isabella; but it is only a few years since it was the principal pit of the colliery; and even to this day the engine of 1838 (improved) is set a going when the flow of water in the Dunfermline Splint workings demand it. No. 12 Pit was sunk about 300 yards to the north of the Isabella. No. 15 is close to No. 12, and Nos. 13 and 14 (the Marion and the James) are operating still further north, the site of the shafts being mid-way between No. 12 Pit and the North British Railway. Operations have ceased in all the pits in the southern section of the field; and now work is concentrated on the field north of the Isabella, in Nos. 12, 13, 14, and 15 Pits. No. 12 Pit was up till recently only sunk to the Mynheer seam, and the Five-Foot and the Dunfermline Splint seams were caught to the rise by cross cutting through the metals. Just recently No. 15 shaft, which adjoins No. 12, was sunk to the Dunfermline Splint, a depth of 105 fathoms, and this shaft being at a low level it is to constitute the pumping pit of the colliery. To cope with the water a Tanges Quadruple, Direct acting, compound, condensing ram pump, has been erected at the bottom of the shaft, and all the fittings are on the most modem principle. To enable the company to carry out the plan of working No. 15 Pit as a pumping pit pure and simple No. 12 shaft has been deepened, the Dunfermline Splint being struck only this week. By the change a capital hold had been got of the Splint and Five-Foot seams in this part of the field, while the Marion and the James Pits are operating upon all the seams from the Lochgelly Splint to the Dunfermline Splint from the centre of the field to the Company's march on the north. The Marion, the James and the No. 12 Pits are fitted with coupled winding engines, and the two former pits are kept clear of water by a pumping engine of the Worthington type which was erected in 1888. This pumping engine has two horizontal steam cylinders, 19 inches in diameter, and has a 10 inch stroke working to two double acting rams, 5 1/2 inches in diameter. The engine is fitted in the Marion shaft, and it forces 100 gallons of water a minute through a six-inch column. In both the James and the Marion the coals are brought to the bottom of the shafts by the haulage system. The haulage engines are placed at the bottom of the shafts, and every contrivance has been introduced to give speed and ensure the miners of a full output of coals daily. Rarefying fans are in operation at the Isabella Pit, and Marion and James Pits. The fan at the Isabella is a "Waddle", and it ventilates the whole of the workings connected with No. 12 and No. 15 Pits, the quantity of air being exhausted being about 20,000 cubic feet per minute. The "Guibal" fan in operation for the north pits circulates 22,000 cubic feet per minute.

A Section Of The Coal

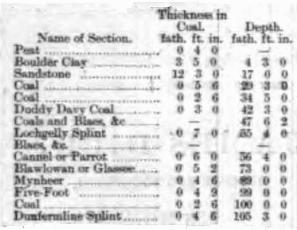

The following is a section of the principal coals struck in the north pit:

In the lower section of the field the seams are even thicker, the Dunfermline Splint being from 4 1/2 to 5 feet, and all the seams are of the very finest quality.

The Quality Of The Coals

The Donibristle Dunfermline Splint, Mynheer, and Lochgelly Splint seams, are all known as excellent household coals all over the country, and the Five-Foot has long had a good market in connection with our great shipping trade. All the apparatus calculated to turn out the coals in the best possible condition to the customer has been fitted up at the pits. The jiggers and screening plant are in continual motion while coals are being drawn at the pits, and so that the treatment of the material may be as effective in the winter as in the summer, the electric light has been introduced and a coal washer has also just recently been erected at the colliery. The colliery was first connected with the North British Railway by a mile of private railway through Moss Morran in 1857.

The Colliery Proprietors and Management

Mr James A. Nasmyth succeeded his father in 1857, and he became sole lessee in 1881 on the retiral of his then partner, Mr G. J. P. Grieve, son of Mr George Grieve.

The Village of Donibristle

The village of Donibristle has not kept pace with the developments at the colliery. This is due to the fact that the northern pits are within easy reach of the Burgh of Cowdenbeath, and there the proprietors and several of the workmen have built a considerable number of comfortable houses. The miners of Donibristle have always been strong on education, and in the early days of the Colliery's existence a school, of wonderful dimensions for the times, was built. The old Colliery School gave place to a spacious new building after the passing of the Education Act, and the reports of HM. Inspector show that Mr Williamson and his staff do splendid work among the young of the district. The cottagers have always had a love for flowers, and the Horticultural Society, which has the patronage of Lord Moray and the Messrs Nasmyth, tends to strengthen the love annually, and as time passes the plots of ground of the cottagers seem to look better. The villagers are blessed with a plentiful supply of excellent water which is drawn from the springs of the Cullalo hills, and they are fully alive to the advantages of the blessing. The old schoolhouse still belongs to the Colliery Company, and they uphold it as a place of meeting for the villagers. The development of the lower seams of coal by the sinking of No. 12 and No. 15 Pits is being watched with a good deal of interest by the miners. Satisfaction is expressed at the fact that No. 15 has been sunk and No. 12 deepened without the occurrence of a single accident. [Dunfermline Journal 13 July 1901]

The Rise & Progress of the Village of Hill of Beath

If there are some Rip Van Winkles in the Western District of Fifeshire who have been asleep during the last half century and are anxious to have an idea of the great progress which has been made in mining since 1840, they could not do better than make a tour round the Fife Coal Company’s works at Hill of Beath. The late Mr Ord Adams began operating on a very extensive scale at Hill of Beath upwards of 30 years ago. The great engine pit he sunk on the eastern slope of the Hill of Beath was a big venture compared with many of the small pits and clay-mines opened up in many of the districts in Fife. In 1887 Mr David Adams, fully alive to the tendencies of the age, inaugurated the work of extending the colliery on a huge scale by contracting for sinking on the borders of the Hill of Beath and Dalbeath grounds, and the pit put down is undoubtedly the largest pit in Scotland. In 1889 the work passed into the hands of the Fife Coal Company, and the management of this great concern have taken care to complete the fittings of the Dalbeath pit on a scale which makes the works a wonder to the miner who comes from the pits where modern appliances are at a discount and extensive mineral development is not aimed at. Instead of following the old custom of sinking two shafts, the one a short distance from the other, a single shaft 26 feet by 10 feet has been put down to the coal seams. The shaft is divided into two by a strong wooden partition. In the northern division the coals are wound from the Dunfermline seam, a distance of 163 fathoms, by a pair of double-decked cages each carrying four hutches; while in the southern division the coals are raised from the Lochgelly splint by ordinary double cages 115 fathoms. A pair of handsome coupled engines are set aside for each division. The engines have 24 inch and 28 inch cylinders and 12 feet and 14 feet drums, and with scarcely a break during the eight hours the pits are in operation With lightning speed the six full hutches of coals are brought to the surface, where all is bustle and activity. The old turning trams and screens would be of but little use for an output of coal such as that which is being vomited out of the Dalbeath pit, and on the huge platform at the mouths of the shafts Messrs Kesson & Campbell’s, Hamilton shaking screens and picking bands have been erected. There are six jagger machines and eight picking bands in operation, and turn how one will all is bustle. The household coals and steam chews are carried slowly along shoots, where stones and all kinds of foreign material are rejected, whilst the smaller pieces of coal are carried through various machines. From the smaller coals are produced the classes of coals known as chirls, treble and double nuts, beans, peas, and dross. The coals are brought into the bottom of the pit by haulage engines, and when it is stated that the workings are all “dook” workings - that is to say that the seams are all lying at a much lower level than the pit bottom - those who know the difficulties which have to be faced will be inclined to assume that a daily output of 800 tons, which will be increased to 1000 ere long, is a wonderful achievement. The workings are kept free of water by a ponderous pumping engine. The high pressure cylinder of the huge pump is 67 inches while the low pressure one is 84 inches. The pumps are 2 inches in diameter and between 2 and 3 tons of water per minute are raised. The winding and pumping engines are the very best of workmanship and supply practical evidence of the quality of the work turned out by the maker, Messrs Grant. Ritchie & Co., Kilmarnock. All the tackling for the pumping gear is of the most substantial material, and the haulage apparatus, by which the coals are brought up the “dook” workings to the bottom of the shafts. is constructed on the most approved principles. The old system of lighting by coal fire-lamps or naphtha is abandoned, and at morning and night the works are lit up by the electric light. Judged from any department the pit is a model one and certainly impresses the visitor with the feeling that if further progress in mining is to be made, it will require to be of a very advanced type. The whole works are a credit to the managing partner of the company, Mr Carlow, and Mr Rowan, the manager. It is under Mr Rowan’s immediate supervision the great concern is carried on. Operations at the brickwork, which is contiguous to the colliery, have also been extended in recent years, and while the machinery for turning out this work has been greatly improved, the number of hands have been considerably added to - the result being that the output of the finished article is very much increased.

While extending the works in every direction, the management have not lost sight of the fact that extra housing accommodation would be required for workmen, and the little hamlet of Hill of Beath has in four years developed into a village of considerable dimensions. Old Hill of Beath consisted of some 40 one and two-roomed houses, while new housing accommodation is provided for no fewer than 205 families. The new houses are a great improvement on the old order of things. Some 20 or 30 years ago a number of the Fife mining villages were largely composed of houses of one room, and the hovels quite met the demands. Along the whole line, the one-roomed cribs are being abandoned, however, and new Hill of Beath is a fair sample of what must be the mining village of the future. The houses are airy and well-lighted, and recognising the necessity for making provision for large families, three apartments are provided in a good many of the houses. Drainage has had a good deal of attention, and all that is wanted to make the drainage perfect is an improved system of carrying the sewage after it has reached a point of considerable distance from the village. Happily the County Council have taken up the question and it has been proposed that the perfection of the Hill of Beath system should be attempted in conjunction with the Crossgates drainage works. A tidy house has been built for the manager, Mr Rowan and a school is being erected on a site close to the village. The history of the school is very easily told. The population has suddenly leapt from 250 to upwards of 1000 and the village being situated a mile from Crossgates or Cowdenbeath, Mr Carlow thought that an infant school ought to be opened. One of the houses was formed into a school of one room and a female teacher appointed at the company’s expense. The demand for infant accommodation more than met anticipations, and two houses had to be made into one room. The Beath School Board recognised the necessity for educational facilities in the village some time ago, and resolved to take over the infant school and to proceed forthwith to erect a new school at the south end of the village. The building, which is now in course of completion, consists of two rooms, lofty and spacious, well lighted from sides by large three-light windows. The building will accommodate 120 senior and 66 junior scholars. The infant’s galleries and desks and benches have received the careful consideration of the Board and the architects. Ample means of ventilation are provided at the windows, and Boyle’s inlet ventilators on the walls, with extracting ventilators on roofs have been adopted. The heating is by open fire-places with hot air flues 6 feet from the floor. Separate entrances, lavatories, and cloak rooms for boys and girls and convenient teachers’ rooms are provided. Boys and girls’ latrines are fitted up to the rear, and ample playground is provided. An acre of ground has been taken off with a view of extension, it being intended that the present building should form part of a larger school. The building and grounds are in a forward state, and expect to be ready for opening early next year. Mr John Houston, Dunfermline, is the architect for the school, and, indeed, was the architect for all the houses built in the village in recent years. [Dunfermline Journal 19 November 1892]

Sixty-Nine Years In The Pits – Fife Miner’s Memories of Bygone Days – “The Fordell Paraud” – Twopence a Week School

Sixty-nine years a miner and still hale and hearty enough to enjoy his retirement. This is the record of Mr William King, now resident in Broad Street, Cowdenbeath. Mr King, who is now 77 years of age, has worked in the mines for forty years at Kelty, and though he has been about twenty years at Cowdenbeath his heart is still in Kelty, and at every opportunity he is to be met with at Kelty talking to his old cronies. A feature of his long life as miner is that he has always been working for a Carlow, and has retired under Mr Charles Augustus Carlow. Mr King related his experiences to a representative of the "Telegraph and Post". The son of Mr David King, of Fordell, a miner, he first saw the light of day in that village.

Slaves in Fordell - Fordell is one of the earliest mining villages in Scotland and in Britain, and at one time, according to tradition, the miners of Fordell were slaves, and were chained to their work.

By and by they were emancipated, and to commemorate their emancipation they held a holiday with a procession every year, which came be known all over Fife as Fordell "paraud."

This function ceased a few years ago, but William King says that previous to that time he cannot remember any year without the "paraud." That was a great day, for, headed by the brass band, a company marched to the "Big Hoose " on Fordell estate by way of the mineral railway to St Davids, a private mineral railway belonging to the Fordell Coal Company, and they returned after being treated by the owner, mostly always the Countess of Buckingham.

A deacon was chosen for the parade, and one of the duties or privileges of the deacon was that he could sell whisky in his dwelling-house for six weeks prior to the "paraud" and six weeks after it had passed

That was a long time ago, but Mr King remembers at least one deacon, whose name was Adam Archibald. In front of the procession was always a man dressed like a cavalier on a white horse, an honour held for very many years by Mr Japp, whose widow still resides in West Broad Street, Cowdenbeath.

The Band - In close association to the "paraud" comes Fordell Brass Band, one of the earliest brass bands in the county. Mr King, who was born 1851, states that he cannot remember Fordell being without its brass band. He cannot exactly vouch for the truth of it, but he got it as being the truth, that when the band was first organised there were twenty-one applications for instruments, and of the twenty-one, twenty wanted to play the big drum.

He can tell many stories of the band, especially how they got nicknamed the Herring Band. That was occasion when after they enticed a herring cadger into a public-house they stole his herring, hiding them in their different instruments. When the cadger arrived at the next village and was asked for herring he found his boxes empty. It is said that on their way home the members of the band started to throw herring at each other, as in the manner of a snowball fight, and got the name of the Herring Band. Some of the members of the band in his early days were Geddes, Woods, and Walter Japp.

His Schooling - Mr King got the little schooling he did get from the late Mr Currie, of Fordell School, deceased many years ago, but to the time of his death a great favourite in the district. He was later schoolmaster in the nearby school of Mossgreen, a position held by his son James, who retired a few years ago. It was so long ago, and his school days were of so short duration, that Mr King does not remember the exact amount the scholars paid for their education in these days, but he remembers some paid twopence. These pennies had to be paid every Monday morning or the pupils were sent home. "No pennies no education,'' was the order of things in these days.

When he was two months short of being nine years of age he was sent to work in the Burnside Pit, Crossgates, but in order that he could get started he had to say he was nine years of age. At this time the family had removed to Crossgates, and he commenced to work with a miner, James Allan. In these days each man got his "turn" of hutches, a man's "turn" being four per day. King being only a lad, only got a quarter turn, and his presence in the pit was really all that was asked from him. His pay was 7 1/2d per day, and at that time the wages of men were from 2s 6d to 3s per day. Of course, he said, the cost of living was much less than it is now. For instance, one could get a pound of fresh butter for 8d. and other things were in the same proportion of cost.

Drawing pictures - "In the pit I did very little," he said. "I could not do much, being barely nine years of age, and Mr Allan made me a seat front of the waste, and he used to draw a duck or some other animal in chalk on the blae face, and I was occupied trying to draw these birds or animals all the day. I remember the first day I went to the pit. I was to meet Mr Allan at the end of the street at five o'clock, and I was so eager to go that I am sure that I was there about three o'clock. At that time there was small school in the village with a headmistress, Miss Bengall. It was then I first became acquainted with the Carlows, and I was destined to be associated with them all my life. The manager at the Burnside Pit was Mr Charles Carlow, the grandfather of the present Mr Charles Augustus Carlow, and I used to go to school and be a playmate of the late Charles Carlow, his father, the family residing not far from where my father stayed at Crossgates.

A School Fight.- "I always remember one incident in the life of Mr Charles Carlow. It was one day we boys got some money, and with it we bought some sugar whistles, and each of us boys got one, but Charles Carlow, being a bigger boy, wanted two. I said he was not going to get two, and there was a fight, and the result of that fight was that the future managing director of the Fife Coal Co. got his nose bled, but not two whistles.

Mr Carlow and I were always friends, and many a pleasant talk and many a sovereign I got from him. I met him one day in Edinburgh, when he left a companion, telling him he wanted to speak to an old friend, and when he left me he gave me a sovereign. I did not tell him I was bound for Musselburgh Races, but the sovereign gave me and my pal a good time that day. One day when I was walking along a road in South Wales, Mr Carlow passed with some gentlemen in a carriage. He saw me, and stopping the carriage he came back and asked what on earth I was doing there. After a pleasant talk about old times, he again left me with a nice sum of money to enjoy myself. I had a good friend in Mr Carlow, as also had many old man of Kelty.

The Old Pit. - "I was destined to keep in touch with the Carlow family all my life. I was only a lad when father removed to Kelty, where I was for the long period of over forty years. At that time there were only about three hundred people in Kelty, and there was only one pit, namely, the Old Pit, situated near the present Gas Works. That pit belonged to the Earl of Moray, and the manager was Mr James Terris, grandfather of the present Parish Clerk at Cowdenbeath, and father of the late Town Clerk and of Mr James Terris, of Dullomuir. Mr James Terris was the cashier at the pit and a Mr Moodie was oversman down below. Mr Moodie, who was the father of Mrs Fortune, Cowdenbeath, was drowned in a pit at Alloa years afterwards. Mr John Terris was clerk in the office, but he died when quite a young man, and his brother, Henry, was in charge of the colliery store. Later a coal company composed of Goodalls and Naysmiths took over the Earl of Moray's coalfield at Kelty, and the manager was Mr Johnstone from the Carron Coal Co., who brought with him an under manager, Mr Borrowman.

A Long Day. - "In these days the miner had a very long day, and got very little for it. I was only a lad, of course, when we went there, but I remember the miners worked from five o'clock in the morning till four in the afternoon. I got to be a driver, and had longer hours, for pony drivers had to take great care of their ponies. After the pit was stopped we had to clean our ponies and wash their feet and feed them. To let you understand how long we worked, I have just to tell you that in these days our postman, Mr Wilkie, came from Kinross with letters in the morning. He stayed during the day at Kelty working as a gardener. At eight o'clock at night he went through the village blowing a horn, which was a signal for those who had letters post to come out to him with them before he returned to Kinross. Well, if we were home before Mr Wilkie blew his horn we had time to get cleaned and have a little recreation. If we were not it was a case of getting our dinner, washing, and going to bed, to get up the next morning for our work at five o'clock.

The Fife Coal Company. - "I now come to the time when the Fife Coal Company took over, for the other company did not last long. Mr Johnstone and Mr Borrowman left and the new manager was Charles Carlow, my old school mate. He set out to develop the coal and new pits were sunk. I believe that the making of the Fife Coal Company was the sinking of the Lindsay Pit, still going strong, for they sunk it in a veritable coal bing and the company never turned back after that day. They sunk two pits at one time, the Big Pit and the Wee Pit, and as they went down they connected the two that they could get ventilation and could get coal that paid expenses as the sinking was going on. When Mr Carlow died Mr Charles Augustus Carlow took office, and I have wrought under him, so you see I have had strong connection with the Carlow family all my life, and I have been an employee for all the time the Fife Coal Company have been in existence.

For sixty-nine years I have been miner and now my time for a rest has come.

The other day I got a very pleasant surprise, for Mr Donnachie, with whom I have worked for a long time, came to see me and in the name of a large number of fellow workers he presented me with a wallet of Treasury notes. I cannot thank them all for I don't know them all, but I want you to do it for me and tell them I appreciate their kindness very much. I am now 77 years of age. I have had a family of twelve, with forty-five grandchildren, and the other day when they started to count my great-great-grandchildren and counted twenty-three, I told them to stop. [Evening Telegraph 10 January 1928]

100 Years Old Tomorrow - Cowdenbeath Man's 50 Years in Pits - His Story of Gold Rush in Fife

Mr John Ford, Rose Street, Cowdenbeath, celebrates his hundredth birthday tomorrow. He was born on the 27th of March, 1828, and during his life has not wandered far from the place of his birth. Mr Ford is a native of Halbeath. When quite young Mr Ford came to Crossgates, where his father found employment at the Prathouse Pit on the Fordell estate, and after some little schooling was apprenticed as a cobbler. However, he forsook the cobbler's shop for the coal mine. He remained a miner for over 50 years and retired about 30 years ago when he was employed in the Raith Colliery, Cowdenbeath. He has been resident at Cowdenbeath for about 40 years. He resided at Kelty for several years, when he was employed in the coal pits. He has a wonderful memory and can recall incidents of his early years even better than he can recall incidents of a later day. He remembers the day when the late Queen Victoria passed through the village on her way to Balmoral and when the stage coach horses were changed at the Inn, Cowdenbeath. He recalls the first entry of a train at Crossgates Station, when according to him, the sound made by the engine, was like "the killing of a pig." John was married by the Rev. Dr. Ferguson of Beath Church in 1854, when he was in his twenty-seventh year. His wife died 20 years ago. His first-born died, but the second of the family is still alive and in his seventy-second year and resident at Kelty. He has some very interesting reminiscences to tell, and the most humorous is his experiences in the rush for the "Lomond Hills gold mines." This took place when he was a young man, and hearing of the great find of gold at Kinnesswood, he decided to try his luck there. He invested in a new pair of boots and made off on the long walk of fourteen miles and soon he was joined on his arrival by hundreds of others out to get their fortune on the banks of Loch Leven. Alas! He never came across gold, and hearing of two men not far away who had made a "strike," he went to investigate their good fortune. After some persuasion they allowed John to have a look at their gold, when he had to inform them it was worthless, as it was only sulphur iron or sulphur pyrites found in the vicinity of iron ore. Then commenced the sad "trek" home. He has always been a follower of sport and even now he is interested in the doings of Cowdenbeath football team. [Evening Telegraph 26 March 1928]

Fife Centenarian Dead - Cowdenbeath Man's 50 Years in Pits. - His Story of Gold Rush in Fife. - Cowdenbeath has lost its centenarian miner, Mr John Ford, who passed away at his residence in Rose Street. Mr Ford was stated to hold a record, in that he was the only Scottish miner who had reached the ripe old age of 100 years, and who was employed in the mines for over 50 years. A son of Mr William Ford, colliery winding engineman, John was born at Halbeath, near Dunfermline, on 25th March, 1828, but it was not long before the family removed to Crossgates, where father became employed as a winding engineman at the Pratthouse pit, near Pratthouse Farm, on the Fordell estate. When John left school he was apprenticed to the village cobbler, but he did not stay long at that profession, the only light available in those days was given by candle, and this hurt his eyes so much that he had to give up the cobbling profession, and he went to work in the local mines, a work carried on for over 50 years. Kinross Gold Rush - He was in Crossgates in the year of the rush for the Kinross "Goldfield." He was quite young when that took place, and he was one of the first to arrive at the "diggings" at Lochlomond Hill, behind Loch Leven. Securing a new pair of boots, he marched 14 miles, but was not alone in his search for a fortune. The hill was soon black with "gold" diggers, but he had not been long there before he made the discovery that the gold was only iron sulphur, or what is chemically called sulphur pyrites. Then he marched back to Crossgates without his fortune and without a sole in his boots. John remembered distinctly of how the first train entered Crossgates, the engine making a noise as though someone was "killing a pig," and he remembers the passage of the late Queen Victoria through the village on her way to Balmoral when her horses were changed at the Cowdenbeath Inn. He was married by the late Dr Ferguson, of Beath Manse, in 1854, when he was in his 27th year, according to the entry on his marriage certificate, and this was the only certification that he had reached the age of 100. John remained in the village of Crossgates until 1877, when the family went to Kelty. He then started to work in the Lindsay Colliery, which had been newly sunk by the Fife Coal Company. A Wonderful Memory – He eventually came to Cowdenbeath, and was employed in the Raith Colliery, but after working for a few years he had to give up working, because of failing eyesight. Just before he died he had a wonderful memory, and could recall with ease incidents of many years ago, often much more readily than incidents of recent years. He celebrated his 100th birthday in March of this year, when, in company of relatives, he took an active interest in the celebrations. He was very hale and hearty on this occasion, and during the afternoon he sang a song. He leaves a large grown-up family, his wife having preceded him about 20 years ago. [Evening Telegraph 28 September 1928]